Interview with A. Sivanandan and Jenny Bourne, conducted by Alice Nutter, for The Magazine of No Value

“I am always guided by a famous thing that Camus said,” explains Sivanandan halfway through our conversation. “Camus was writing to a German friend during the war, and this German friend had become a Nazi and he wrote to him and said: “I want to destroy you in your power without mutilating you in your soul.”

Sivanandan manages to sound unpretentious whilst quoting Dylan Thomas and Pindar between sips of tea. He throws art and ideas into conversations the way other people chuck in “Y’know what I mean” and he makes you want to read writers you’ve never even heard of. Sivanandan is an activist who thinks like a poet. A critic who creates; his writing slices through to the core of whatever he’s dealing with, whether it’s the racism directed at refugees or capitalism rewarding the few at the expense of the many. He’s polite and friendly but not soft, and despite having a huge impact on Britain’s radical politics he’s nowhere near becoming a household name. Asian Dub Foundation sampled him for their last album Community Music but he’s unlikely to turn up on stage and take a bow. Now in his late seventies Sivanandan hasn’t courted fame.

If Sivanandan is not as well known as some left-wing figures, it is because his politics are too uncompromising for the mainstream media. His essays had an influence way beyond their initial print runs: circulated as dog-eared photocopies, they were the focus of intense political dispute. (They have since been collected and published in two volumes.) Sivanandan has always addressed the essential dilemma of how to fight without loss of humanity. Returning to Camus, Sivanandan shakes his head and says: “How will I fight a political enemy? How will I shoot my reactionary father but with a tear in my eye?” How indeed.

It would be unfair to talk about Sivanandan without bringing in Jenny Bourne and Hazel Waters. The three of them are a collective and the backbone of the Institute of Race Relations; a respectable title for a radical organisation which, in fact, used to be very establishment before it was hijacked by Bourne, Waters, Sivanandan and other workers in the early seventies. They also produce Race and Class, a quarterly offshoot of the IRR edited by Sivanandan, which has drawn in some of the most significant political and intellectual thinkers of the post-war period. Those who have sat on its editorial working committee or council include John Berger, Edward Said andOrlando Letelier, Allende’s ambassador to the US, who was subsequently assassinated. Contributors have included Noam Chomsky, EP Thompson and Angela Davis.

Part of what’s important about Sivanandan is that he understands and promotes working collectively. The IRR regularly holds seminars where activists,

thinkers, artists and writers meet up; after September 11th they organised a series of discussions introduced by Sivanandan and Naomi Klein, the result of which was a collection of essays published in the summer on the Challenges of September 11th. Just as the Beatles and the Sex Pistols produced their best work when they were surrounded by radicals, musicians and artists, Sivanandan continues to be relevant because he’s always willing to work with others. How many other sectagenarians appear on a subversive pop album?

Ambalavaner Sivanandan was born to a Tamil family on 20th December 1923

in Colombo, Sri Lanka (then Ceylon).

His father, whom he writes about in his novel When Memory Dies, was originally from a peasant family and had worked his way up to the rank of Postmaster. His sense of honour and his way of always fighting for the rights of others was a huge influence on Sivanandan but he was intolerant of mixed marriages.

When Sivanandan fell in love with and married a Catholic Sinhalese girl, father and son were estranged for years. Sivanandan was politically active at university and taught briefly before going into banking. He got a job as a bank manager but it didn’t quite fit him:

“I became a bank manager because I had to help my brothers and sisters, my whole family, out of poverty,” says Sivanandan. “So that my politics had receded except that I helped to start a bank clerks’ union even when I was a bank manager, so that rebellious tendency was still there.”

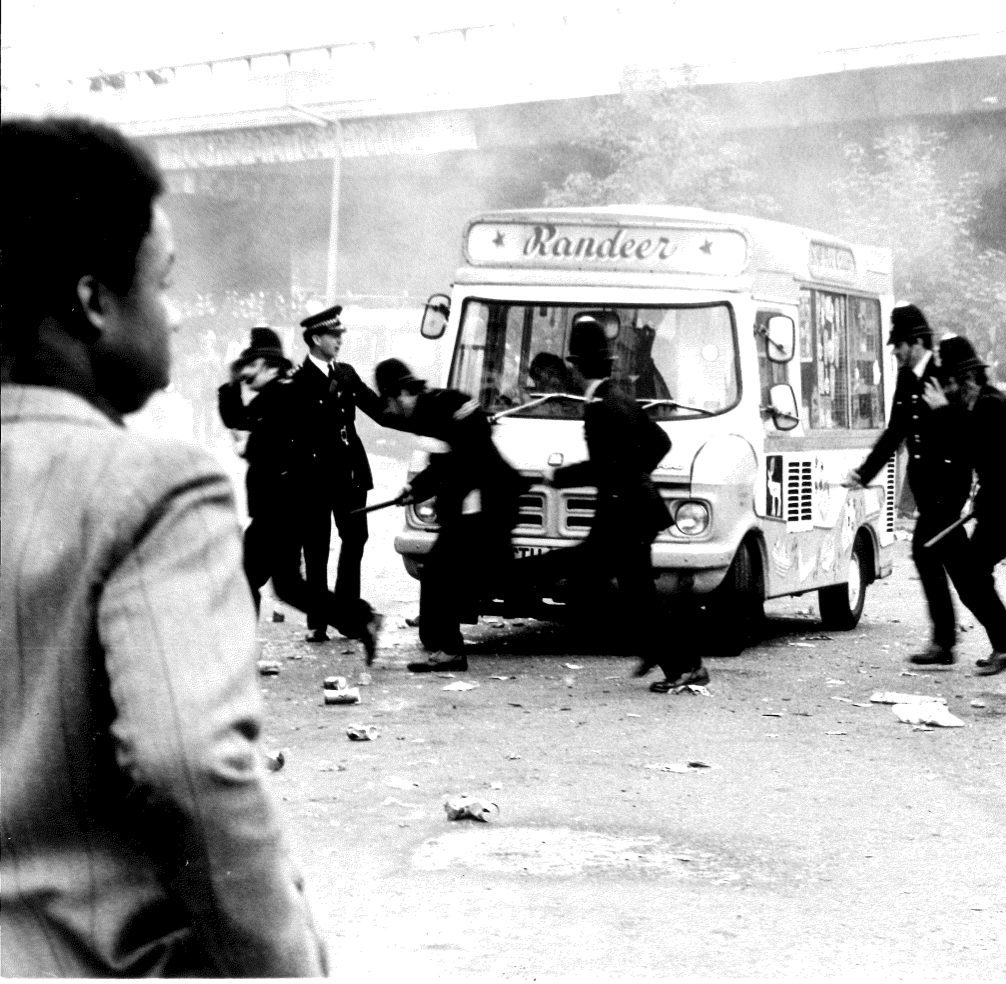

The outbreak of the government-sponsored Sinhalese pogroms against Tamils in 1958 changed the course of Sivanandan’s life. During the violence he had to dress as a policeman to lead his family through the mob to safety. Sickened by the hatred around him, he escaped to the UK with his wife and three kids, landing into the midst of theNotting Hill riots in London.

“That was my Damascene conversion if you like,” says Sivanandan of the Notting Hill riots. “At that point the visceral, the political and the emotional and all that came together and I hated what human beings were doing to each other, and so I decided that I won’t gointo banking, I won’t go into the jobs I’d done… I want to fight racism, I want to fight colonialism… you know the sort of young man’s dream of fighting all the injustices of the world.”

London didn’t provide a warm welcome for the Sri Lankan refugees. Sivanandan got a job as a tea boy in a library and his wife took work as a typist and together with their three kids they shared one room. The marriage didn’t survive the strain and Sivanandan was left with the children. “I didn’t even know how to cook when my wife left. bringing up children alone made a woman out of me.”

‘No blacks, coloureds or Irish’ notices were still in the windows of London boarding houses. Then – as today – refugees weren’t made welcome. “I lived in Notting Hill for a while in rented accommodation where they put all the blacks into the basement. I had terrible experiences. Then I answered an advertisement in the New Statesman about renting a flat in Chalk Farm, I rang up this lady and I thought ‘New Statesman; my sort of journal, on the left, fellow socialists… and I rang up this lady who was renting out the flat, and because by this time I knew that there was so much racism around. I started off by saying I am from Ceylon, and I would like to rent out this flat,’ and she said, ʼ Er, I’m not prejudiced about you being from Ceylon or anything like that but you did say that you had three children?’ And I said, Yes.’And she said, ‘Oh well we have only two bedrooms and I don’t think it’s enough. So I’m sorry we can’t rent it to you.’ This was such a humbug answer that I rang up half an hour later, absolutely livid and I said, ‘It’s me again, please can I have

the flat now?’ And she said ‘What has changed?” And I said ‘I’ve murdered one of the little buggers!”

This absolute refusal to accept flannel and half-truths is what marks Sivanandan out. Part of the reason he came to Britain in the first place was because he’d been educated under British colonial rule with the line that Britain somehow stood for higher values of fairness and justice: “The British ideals were our ideals: free speech, democracy, humanitarianism, all the universal values of modernism. All the enlightenment stuff, we bought it… but I

also knew that the reality was not quite right back home but when I came here it I was a staggering realisation that the reality was completely different, in fact the opposite. I suppose in a way it is a very ironical thing; our fight ever since has been to return to Britain the values which it preached to us without itself practising them. That may sound a little pretentious. That is where British imperialism, British colonialism made a mistake; the values that they taught us and didn’t live up to became our values and we took it so seriously that we now challenged Britain to live up to them.”

Sivanandan qualified as a librarian in 1964, and was employed two years later by the Institute of Race Relations, an organisation dedicated to the study of race relations. Originally a branch of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, the IRR was funded by big business Shell, Nuffield, Rockefeller and Ford among others. The IRR was supposed to be devoted to the objective study of race relations. After the 1962 Immigration Act it began to take the government’s view that controlling immigration was necessary to improve race relations. Most of the early studies looked into Africa and other newly developing countries with a view to seeing how business could invest there.

Sivanandan took a pay cut to take the job at the Institute because he understood that it was open to subversion.

“There was an air of genteel decay about the whole Institute when I went for the interview. People on the council were the lords and ladies of humankind these were the people who had ruled me and my country. So I already had an understanding of what they were up to. I felt that I must – to use Pindar’s beautiful phrase ‘exhaust the limits of the possible.’ I cannot shake the world but I can move pebbles which might bring on an avalanche.”

“We had people saying things like ‘we need to have fewer of them for better race relations’,” adds Jenny Bourne who went to the Institute as a researcher in the early ’70s. “They were also saying ‘Unless we make the situation right we’re going to have social dislocation, which will cause problems and that will be bad for the nation.’ Not bad for the

victims but bad for the nation’.”

In 1972, Sivanandan and his allies led a coup against the old guard. Their plan was to create a new IRR: “a sort of think- tank, a think-in-order-to-do-tank for black and third world peoples”.

“It was a Pyhrric victory,” says Sivanandan “We won the battle for the Institute but the management council had the money and they left with it. So we moved to an old warehouse here in Kings Cross, and a lot of the black community supported us during the struggle, putting out leaflets about it and so on and so forth, so we got them to move the library and they kept the library open in the evenings for themselves, so the library became a very important part of education of black people.”

The run-up to the bloodless coup was a political struggle which saw the state and the Institute’s council try to stave off the mutiny with bribes and threats. “So we were having to learn how to deal with and politicise each other,” says Jenny Bourne. “And every day something would change, somebody would come with a bribe, offer to publish someone’s first novel, buy the library off… so

everything that happened was politics. It was a very happening place.”

In the midst of fighting for control of the Institute the workers were also closely involved with the Black Panthers and welfare programs. “We were trusted by the black community and then the black community was on form,” says Sivanandan. “We were actually given money by a big London charity to kind

of, on their behalf, give it out to black groups,” says Jenny Bourne. “They didn’t know how to relate to black people so they needed us as pimps. In that way we managed to fund quite a lot of welfare work being done by the black power movement.”

“We managed to change the whole way the Institute had been run internally,” she adds. “When I’d gone there it was completely hierarchical. I was on the bottom, the only people below me were the people who answered the door and answered the telephone. Everybody was kept in their place, we were not allowed to go to council meetings, it was too frightening to talk at staff meetings…to me the most important thing was that we began to be able to run the Institute collectively, and it was a real collective where we all knew each other’s strengths and weaknesses and all helped each other to grow, to change and to grow along with the Institute, so we could all do what we wanted in the best way for the organisation and for ourselves. And that, to me, was an important political development. A lot of people talked about being a collective in a kind of mouthy sort of way, but I think we really were.”

After hijacking the Institute they set up Race and Class and appointed Sivanandan as editor. Various academics who’d been supportive during the storming of the Institute’s gates were incensed that a librarian (and a former tea boy at that) was going to edit a radical journal. That was a post they had their own eyes on. So the next fight was against those who wanted control of Race and Class for their own ends.They threw all the academics off the board and invited the radicals in.

“What happened was really important for my politics,” says Jenny Bourne. “This journal which was called Race and really boring, we turned it into Race and Class. It was a

third world journal which looked to all these liberation movements. We brought in a whole lot of people that we’d met; people who’d been involved in liberation movements, some of the greatest people on the left throughout the world. I actually think I have been honoured to have been working with those people after 1974, and getting them involved in

our struggle and that in a way gave us a whole new perspective.”

Sivanandan proved to be a great editor and essayist. Like many great essayists, Sivanandan’s best work is always a form of attack. Many credit him with the demise of racism awareness training – fashionable in many liberal and left-leaning authorities in the early 1980s – which he demolished in his essay ‘RAT and the Degradation of Black

Struggle’. Whilst others were saying that the root of all problems was language and the way it was used, Sivanandan pointed out that as long as black people

were economically disadvantaged, trapped in ghettos and scapegoated under capitalism, then concentrating on labels was something of a side issue. And one that provided jobs for black professionals but was politically damaging to the community as a whole. His 1990 essay, ‘All that Melts into Air is Solid’, a stinging attack on the trendy betrayals and selfish limitations of the new left gathered around the once popular magazine Marxism Today,

remains one of the most substantial and influential attempts on the left to halt the drift towards consumerism and compromise. While Marxism Today pronounced the fall of

the Soviet Bloc as ‘the end of history’ and claimed that we should all embrace capitalism, Sivanandan argued that history was an ongoing battle and that those living in degradation and poverty didn’t view capitalism as an all conquering hero. After Marxism Today had shut up shop, ex-editor Martin Jacques appeared on TV claiming that the ‘tiger economies’ and Asian-style capitalism was the way forward. A month later the ‘way forward’ collapsed when the tiger economies crumbled and Sivanandan was vindicated once again.

One criticism made of Sivanandan by the left establishment is that he’s out of time and that New Labour rather than struggle is the way forward. The problem isn’t that he’s anachronistic but that he’s ahead of his time. He was one of the earliest critics of globalisation, bringing it to the fore as early as 1979.

“I wrote a pamphlet on imperialism in the silicon age which was a paper that I gave at a

conference in Berlin. That was the first time I got up and talked about the new certainties of globalisation, about how capital was moving.”

Activist and scholar Edward Said has pointed out that immigration is the symbol of the 20th century, saying that if you want to look at what capitalism does to people’s lives,

look to migration. In the last half of the 20th century there have been vast numbers of people dislocated by war, famine and economics. As politicians throughout Europe continue to scapegoat refugees, Sivanandan has rightly argued that the distinction

between economic and political refugees is bogus “Globalisation displaces people, I call

it economic genocide by stealth. There’s no such thing as an illegal migrant, there’s only an illegal government. And those illegal governments are our governments back home which have been set up by Western capital. So if you have a politics, a global pro-multinational politics of the West, which sets up puppet dictatorships, reactionary

regimes – or if it doesn’t set them up it maintains, or helps finance these regimes in the interests of oil, in the interests of getting cheap labour, in the interests of multinational corporations – then if you go over to the third world and set up these regimes and they become politically repressive, then obviously the people who are being oppressed have got to get out of that country. So it is your economics, the governments of multinational corporations, that makes for our politics, which makes the migrant come over here. So he’s not an economic migrant, he’s a political migrant. You can’t distinguish in our third world countries between the politics and economics; the politics is the economics.”

“The west is quite happy to take in economic migrants if they are businessmen (with the requisite £250,000), professionals, or technologically-skilled. It welcomes the computer wizards of Silicon Valley of Bangalore but does not want the persecuted peoples of Sri Lanka or the Punjab.”

Hostility towards refugees is no longer colour-coded; people don’t have to be black to be poor, they just have to be born at the wrong time, in the wrong place under an unjust system. The Balkanisation of countries, where

nations split into hostile factions, has resulted in floods of refugees. They are often discriminated against on the grounds of poverty and the term that’s bandied around to describe the hatred directed at them is ‘xenophobia: the fear of strangers.’

“I’ve always rejected the term xenophobia because it’s a harmless sort of word for a very harmful attitude. What is xenophobia? Fear of strangers. Third world people never had fear of strangers; it’s European white people who had fear of strangers. There’s a famous saying about Africa: The missionaries came to Africa with a bible in one hand, but when they left they left the bible and took the land.’ So there’s no fear for us of being hospitable to strangers; it’s a European disease. Also xenophobia has the innocuous look of something that is natural; it’s as if it’s natural to be afraid of strangers who are unusual and not used to your manners or your circumstances…

“In the act of using the word xenophobia, it detracts from the seriousness of the whole thing, so what we have said is, that it is xeno fear of strangers in form, but racist in content.

You don’t have to have a black face to be poor, from the Balkans if you like, not wanted… so what we’re having now in the global arena is xeno-racism.”

“It’s demonisation. The cultural demonisation of asylum seekers takes place before the law comes into place. Capitalism moves in mysterious ways, its miracles to perform. There’s a collective subconscious about capitalism which allows it to use the cultural feeling, the cultural instance, the cultural dynamics of a people in order to soften them up for the economic exploitation to come. In an old democracy like Britain it’s a blotting paper society that absorbs and negates opposition.”

Culturally the Arab world is seen as the other’ and so the plight of the Palestinians under Israeli apartheid has long been ignored and glossed over.

“If you have experience of being oppressed as a movement that must open you up to the oppression of me as a black man, otherwise what is the point of having the experience and missing the meaning? The situation in Zionist Israel is exactly that. These are people who have suffered so long and so terribly and yet these are the people themselves who are becoming the oppressors. What’s the point in experience if you miss the meaning? And that’s where Camus thought comes in, that it is why we must destroy people in their power but not mutilate their soul.”

According to Sivanandan, America’s reaction to September 11th is a classic example of not learning lessons. “The world is in danger from America economically, politically and, now, militarily. Globalisation has engendered a monolithic economic system governed by American corporations that hold nations in thrall. September 11th has engendered a monolithic political culture that holds that those who are not pro American are either terrorists or valueless and therefore surplus to civilisation. Together, they signal the end of civil society and the beginnings of a new imperialism, brutal and unashamed.”

“On a more philosophical level, one would have expected that the suffering inflicted on the American people after September 11th would have sensitised them to the suffering of the poor and the deprived of the world. But, alas, they have had the experience and missed the meaning. Worse, they have denied all meaning to their own suffering by inflicting it upon others.”

“We are connected to one another, in the deepest sense, through our common pain. When we lose that connection we lose our humanity.”

All the way through our conversation Sivanandan kept stopping to ask if I needed more tea, to ask his colleagues if they’d ordered their sandwiches, to make

sure they weren’t waiting for him to finish the interview before they had their lunch. I had a cold and it was all I could do to stop him from making me a hot Lemsip. He never acts like a big shot; treating people well is part of his nature as well as his politics. Sivanandan believes he’s kept his humanity by battling for the rights of others. The IRR is as well known for highlighting the deaths in police custody and abuses of power as it is for pushing radical thought forward through Race and Class. You could never accuse Sivanandan and his colleagues of ignoring the big picture or missing the all-important human details. The thing about Sivanandan is that whether he’s quoting literature or exposing the Emperor’s new clothes, he always makes sense and he always takes politics back to the effect on people’s lives. That’s what’s important to him; what the decisions made up on high actually mean in Brixton or in the sweat-shops of Indonesia. He’s blunt, sharp and ferocious and loves art and friends as much as he hates what people

are capable of doing to each other. He’s expansive and warm but he’s also an attack terrier, Over the years he’s developed a reputation for being clear- headed and incorruptible. He’s the antithesis of those obsessed with fame and financial gain and if he does appear in the media it is always to make a point rather than to sell himself

“I learned to reply in a way that they wouldn’t edit me out like the David Dimbleby programmes after the ’81 riots, and on some other programme about the Scarman Report. Because there is a way of talking where everything you say is so loaded, everything you say counts. So that was a very good discipline for me.”

“I think I always felt that I should be known by my work and not by who I am. Secondly, I always thought that as a director of the institute and the editor of Race and Class, the most important thing about power is not to use it.

“I suppose I’m arrogant but not vain and there is a distinction. I think vain people become celebrities; arrogant people don’t need it. It’s like God he makes the rain and the world in six days and rests on Sunday. I know who I am. I don’t need somebody else to tell me who I am. I think celebrities need that; they need acceptance, they need to be validated.”