First published in Race & Class, 19/1, Summer 1977

Two recent events have further elucidated the strategies of the state vis-à-vis the black community and, more especially, the black section of the working class, first analysed in ‘Race, class and the state over a year ago. One is the House of Commons Select Committee Report on the West Indian Community and the other is the 10-month-old strike of Asian workers at the Grunwick Film Processing plant in Willesden in North London. Of these, the Grunwick issue is the more complex and confusing and, if only for those reasons, the more challenging of analysis however risky the exercise of writing history even as it is being made.

A GRUNWICK

Grunwick processes photographic films and relies a great deal on the mail-order business. It is estimated that around 90 per cent of those on the processing side are Asians, many of them women and most of them from East Africa. The strikers first walked out when a worker was sacked after being forced to do a job he could not possibly do in the time allotted for it. This was typical of the punitive, racist and degrading way in which the management treated the workforce. The strikers, on the advice of the local trades council, joined APEX (the Association of Professional Executive Clerical and Computer Staff). The employers, however, refused to recognise the union and the strike has now centred on the question of union recognition by management since union recognition is a prerequisite to raising the wages from the exceptionally low figure of £25 for a 35-hour week.

The strike has received widespread union support, which is in certain respects unique in the history of British trade unionism. Not only has full strike pay from APEX been forthcoming from the very beginning, but also other national unions, e.g. Transport and General Workers Union, the Union of Post Office Workers (UPW), the Trades Union Congress (TU), and through their encouragement hundreds of local union branches, shop stewards committees, trades councils and others, have given financial and other support. Not only did Len Murray, General Secretary of the TUC, intervene personally in the dispute, but cabinet ministers have themselves been to the picket lines to give their support. After a certain amount of pressure, the UPW took the almost unprecedented step of introducing a postal ban. Although this lasted only four days in the event, it hit management hard since it relies on the mail-order side for 60 per cent of its business.

At first it looked as though Grunwick was to be the rallying point for the labour movement to prove its commitment to black workers. But what is more apparent now is that the unions have been carefully determining the direction that the strike should take and the type of actions open to the strikers. It is worth recalling here the comments of George Bromley, a union negotiator for 30 years with London Transport, who in 1974, during the Imperial Typewriters strike of Asian workers, said, ‘The workers have not followed the proper dispute procedures. They have no legitimate grievances and it’s difficult to know what they want… Some people must learn how things are done…The ‘proper procedures’ have in this case certainly been taught and followed to the bureaucratic letter. When the right-wing National Association For Freedom threatened legal action against the postal boycott, the UPW capitulated, arguing to the strikers that they had persuaded management to go to arbitration to the Advisory Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS). But when ACAS called for a ballot of the workforce, management sought to limit it to those still at work and not the strikers- so discrediting the ACAS procedure and the Employment Protection Act within which it operates. Similar bureaucratic procedures, such as appeals to the Industrial Tribunal and recourse to government investigation, have proved equally futile – and, worse, delayed the possibility of effective solidarity action. It was six months before ACAS’s report (in favour of the strikers) finally came out. Nor has the UPW reintroduced its ban, despite its promise to do so once the report was out.

*Under the 1953 Post Office Act, which prohibits ‘interference with the mail’

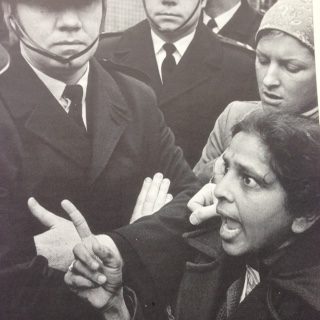

On the other hand, the unions have induced the strikers to stay out by almost doubling their strike pay. But while the unions are keen to keep the strike going at all costs, the strikers themselves have begun to question the conduct and purpose of the unions’ support. According to Mrs Desai, treasurer of the strike committee, ‘If the TUC wanted, this strike could be won tomorrow.’ The workers are belatedly resorting to tactics they urged in the first place, such as picketing local chemists shops (from which Grunwick’s trade also comes) and organising 24-hour pickets.*

Asian workers have over the last two decades proved to be one of the most militant sections of the working class. In strike after strike – Woolf’s, Perivale Gutterman, Mansfield Hosiery, Imperial Type writers, Harwood Cash and others – they have not only taken on the employers and sometimes won (limited) victories, but have also battled against racist trade unions which have either dragged their feet or quite often denied them the support they would have afforded white workers. The Imperial Typewriters case was the most blatant.

*Since writing this, APEX at its Annual Conference came out firmly against a return to

collective bargaining

In May 1974 Asians at Imperial Typewriters (a subsidiary of Litton Industries) went on strike over differentials between white and Asian workers. The unions refused their support and the strikers, supported by other black workers, had to fight both union and management (bolstered by the extreme right-wing party, the National Front). Over the Grunwick dispute, however, the unions have been unusually supportive of the Asian workforce. Some commentators on the left have traced the union change of direction to a sudden change of heart: it had come upon them (the unions) that racism was a bad thing and should be outlawed from within their ranks. But why this ‘change of heart’? In the first instance, of course, the basis of the Grunwick dispute is the unionisation of the workforce and it is therefore in the interests of the unions (and indeed their business) to recruit workers into their organisations. This is the most obvious reason for union support of the strike. But the inordinate anxiety to unionise the workers must be seen in the larger context of government-trade union collaboration in the Social Contract. In effect what the Government says to the workers in the Social Contract is: ‘we are in a time of great economic crisis, with increasing inflation and galloping unemployment. The only way we are going to solve the problem is by keeping wages down. But we can do this only with your agreement to put up with hardships. So if you agree not to use your power of collective action (the only power you really have to improve your conditions), we will in turn see that you are protected from the employers taking advantage of your restraint. We will, in return for your abandoning the right to collective bargaining, give you statutory safeguards to keep the employers at bay.’ Hence the Employment Protection Act 1975, the Trade Union and Labour Relations Acts of 1974 and 1976, the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 and the Equal Pay Act 1970 (enforced in 1975). And, more recently, Michael Foot, Leader of the House of Commons, has inveighed against the judiciary for its apparent anti-union bias. ‘If the freedom of the people of this country – and especially the rights of trade unionists had been left to the good sense and fair-mindedness of judges, we would have precious few freedoms in this country.

The Grunwick dispute, if the other Asian strikes are anything to go by, threatens to blow a hole, however small, in the Social Contract and in the circumstances (of the rank and file of the working class clearly jibbing at a further extension of the Social Contract), one swallow could easily make a summer! To bring the dispute within the Social Contract framework it is first necessary to unionise the Asian strikers, But to unionise a black workforce, it is first necessary to take a stand against racial discrimination. It is necessary to speak to the workers first and overwhelming ‘disability’. The strike’, said Mrs Desai, ‘is not so much about pay, it is a strike about human dignity. Hence, if the unions are to win the confidence of the strikers, and of black workers in general, they have to take an unequivocal stand against the employer’s racist practices. Besides, it is the very fact of colour that has, as so many times before, lent a political dimension to the struggle of the Grunwick strikers – and the unions, as so many times before, are anxious to keep that dimension out, particularly in view of the Social Contract. Additionally, in the overall strategy of the state, the management of racism in employment has, since the strikes of 1972-4, been handed over to the trades unions (and not to the Community Relations Commission). Now that the state has decided that the social and political cost of racism has begun- in the objective circumstances – to outweigh its economic profitability (see ‘Race, class and the state’), the unions are equally anxious to contribute to that effort.

In fact as far back as the TUC Conference in September 1976, APEX General Secretary, Roy Grantham, spoke about the Grunwick dispute in the context of the Government White Paper on Racial Discrimination, which heralded the Race Relations Act. The Act itself, passed in November 1976, is very concerned with employment and in fact extends the application of the new employment laws complaints procedures to the area of racial discrimination. This Act unlike previous race relations acts, has full union backing. This support for the new legislation has been accompanied by increased interest and concern about race relations within the trade union bureaucracies since the 1972-4 period of disputes. After the Mansfield Hosiery strike there followed a whole spate of strikes throughout the East Midlands involving Asian workers in dispute not only with management, but usually with the union and fellow white workers too. Strike committees of different factories supported each other, workers were learning from the examples set in neighbouring cities, local black communities supported the strikers, there was serious debate about the need to set up black trades unions. It is since then that we find proposals for special training on shop steward courses, the establishment of race relations departments in national unions and the TUC and the production of a TUC model equal opportunity clause for contracts. And, more recently, a government race relations employment advisory group has been set up on which the TUC and ACAS, as well as the Confederation of British Industry and the Commission for Racial Equality, will be represented.

But the management of racism in employment is not the only thing that has been left to the unions’ care. They have also been entrusted with the task of selling the Employment Protection Act to the workforce as a whole. The Grunwick dispute encompasses both these functions. What we have, therefore, is not a ‘change of heart’ but a change of tactics to ordain, legitimise and continue the joint strategies of the state and union leaders against the working class – through the Social Contract.

B REPORT ON THE WEST INDIAN COMMUNITY

‘The character of the coloured population resident in this country’, said the White Paper on Racial Discrimination (September 1975) setting out the thinking behind the Race Relations Act (1976), ‘has changed dramatically over the decade.’ Two out of every five of that population was born here, educated here and knows no other country. Discrimination against this section of the coloured population’ therefore was bound to alienate them more quickly and more decisively than their parents – and was a waste of resource and energy. The leaven of energy and resourcefulness’ of the immigrant communities, the Government warned, ‘should not be allowed to lie unused or be deflected into negative protest on account of arbitrary and unfair discriminatory practices.

This warning the House of Commons Select Committee takes to heart in its report on the West Indian Community. It culled masses of evidence from various groups, organisations and individuals, and visited the Caribbean islands to make a study of the natives in their natural habitat. The Committee had previously deliberated on problem areas such as immigration, housing, education and employment. But these were traditional problems of a state in a shrinking economy, highlighted (as opposed to caused) by the black presence, and demanding resolution. Since then a problem has arisen – arisen in the eyes of authority,, that is – which if allowed to escalate could tax the coercive forces of social democracy: the increasing militancy of British-born blacks with nothing to lose and no place to go back to. And it is because the Select Committee turns to examine the West Indian community in this problematic context that the problems of the West Indian community are viewed as a problem for the state. The West Indian community, that is, is the problem.

Or, in the words of the Committee, ‘The alienation of some of the young blacks cannot be ignored and action must be taken before relations deteriorate further and create irreconcilable division.’ But ‘the problems of the young blacks are those of the West Indian community at their point of greatest tension and strain.’ The implication therefore is that in speaking to the problems of black youth it is necessary to speak to the problems of the West Indian community as a whole. And this the report does, specifically in its recommendations. It addresses itself to the special disabilities’ of the West Indian community and even suggests methods of ‘positive discrimination that would help to redress the balance – the balance of society, that is, the status quo so violently tipped by the black presence. In other words, when the social cost of racism outweighs its profitability and threatens to disrupt society as a whole, palliative measures have to betaken. On the question of immigration, for instance, the Committee takes account of West Indian family patterns to advocate a change in the entry regulations to allow the admission of children to join a single parent. In the matter of child-care, the Committee notes that a ‘high proportion of West Indian women especially in the areas of West Indian concentration and among those aged 25-44 years are in employment, most of them full time’. The Committee therefore recommends that ‘the Government and the local authorities should recognise more deliberately the value of the training and employment of West Indians in the social services and, in particular, they should encourage their employment as child-minders and in residential care: that they should actively encourage West Indians to be foster parents: and that they should provide both more extensive training for child-minders and, when it is necessary, more effective training for welfare officers who deal with West Indian families’. In the matter of education, it calls for widespread reforms: ‘special measures to improve the teaching of literacy and numeracy in primary schools’, ‘special attention … to the monitoring of the numbers of West Indian children attending schools for the educationally subnormal (ESN), and the ‘need for sympathetic consultation with parents and of inviting discussion also with representatives of the local West Indian communities’. But the greatest stress of the Committee’s recommendations is on schemes of self-help designed to help the West Indian community tackle its own problems, especially the problems of black youth who ‘are beyond the reach of the normal social services’. To this end the Committee recommends on all issues, the placing of more West Indians in positions of authority and responsibility over their community. Many recommendations therefore involve making sure that West Indians are promoted and encouraged to take such custodial positions as immigration officers at the ports of entry, as teachers, as social workers, as advisers on employment. On the matter of police-black relations, however, the Committee seems to drag its feet, and while acknowledging that the recruitment to the police force had been massively rejected by the West Indian community as a whole, continues to recommend such recruitment.

At the heart of the Committee’s concern is the tacit acknowledgement that the Government’s strategy to integrate the West Indian community into the system has up-to-date produced few results. Despite the large sums of money handed out to black self-help groups, youth clubs, hostels, arts and theatre groups, despite opening up places in higher education to black youth, the West Indian community continues to stand outside the gates. By and large it rejects unemployment benefits and social security, refuses to join the police force, derides Uncle Tom place-seekers and, worst of all, closes ranks as a community the moment any section of it is under attack. And this is the more alarming because large numbers of black youth are being increasingly ‘deflected’ into the type of ‘negative protest that the White Paper spoke of and the 1976 riot of Notting Hill signified. All of which makes the task of integrating the West Indian community that much more difficult – and demanding of special measures. For, in the words of the Committee, West Indians generally are not able to provide facilities for themselves because their community is poor and made up mainly of working-class people and, unlike the Blacks in the United States, largely lacking the professional and business men who could provide the necessary expertise and funds’. This is, of course, in marked contrast to the Asians who are regarded as a self-achieving society with their own businesses, shops, industries and, helped along by a ready-made bourgeoisie from Uganda, are creating their own class hierarchy.

Hence, whereas with the Asian community – a structured, stratified society, in many respects parallel to British society – only a little effort was required to slot them into the system, albeit on a basis of cultural pluralism, in the case of the West Indian community there is the primordial task of creating a stratified society in the first place. How to break up a cohesive community into a class hierarchy as the prelude to integration – that is the problem to which the Committee addresses itself.