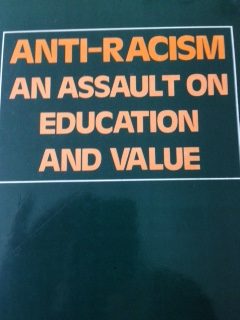

Published in Race & Class 29/1, Summer 1987

Increasingly, over the past year, the Tory government (supported by its satraps in the gutter press) has given up even the pretence of attacking the crucial issues of racial discrimination, police racism and inner-city decay and has gone over to attacking instead of ‘anti-racism’ of local Labour parties and their radical black councillors. Unfortunately, this shift from tackling racism to tackling the discourse on racism (via anti-anti-racism) was a red herring that the Labour Party was bound to follow, given its inability, refusal even, to recognise and develop the inherent compatibility of socialism and black struggle. And it was precisely in the London Borough of Brent that the possibility of such a rapprochement was being held out. But the national Labour Party, in disowning the struggles there, and in implicitly accepting the dominant propaganda that the Left in Brent was indeed ‘loony’, was able neither to ameliorate the stylistic excesses of ‘anti-racism’ nor to validate its vaunted socialist thrust and principles.

Two incidents if Brent focused national attention. First, there was the disciplining of the white headteacher, Maureen McGoldrick, for allegedly telling a Council employee not to send her any more black teachers to fill vacant posts. Second, there was the decision to appoint black teachers to 180 specialist posts as race advisers, which were funded under a government scheme aimed at areas of special deprivation and high ‘ethnic’ concentration. But, in the hands of the media, Brent has come to symbolise left-wing totalitarianism – a place where ‘thought police’ and ‘race spies’ are used to hound and persecute de-cent, English teachers who just cannot get on with the job they are paid to do because of unwarranted political interference.

It is a view which had met with little, and largely ineffective, opposition. Event those left analysts who tried to disentangle the threads of the Bent debate have, by and large, confined themselves to ‘anti-racism’ and missed, therefore, many of the wider ramifications of the struggles in Brent over education. For, though the issues came to the fore in Brent over increasing the appointment of black teachers, the issue itself was not black teachers per se, but entrenched class disparities in the provi-sion of education. In other words, an issue of class was being fought out on the terrain of race.

Every ‘fact’, therefore, needs to be analysed twice, once on the touchstone of face and once on the touchstone of class. To do that, however, it is first necessary to look at the social geography of Brent. The most startling thing about Brent is that it displays within one borough a microcosm of Thatcher’s ‘two nations’. Though, statistically, Brent as a whole has some of the worst housing, highest over-crowding, and highest unemployment in all London, the deprivation is not equally distributed. On the contrary, the north and west of the borough (north of London’s North Circular Road), formerly the Borough of Wembley, is predominantly middle-class with a high degree of owner occupation. It is an area which tends to return Tory or Alliance councillors and still campaigns, even now, to return to its former 1960s boundaries, so as to maintain the area’s sub-urban essence, free from the contamination of the adjacent inner-city wards. All this is not to say that there are no black residents in this part of the borough. There are northern wards which have many black residents as do the more deprived wards of the south and east. But in the north and west, the majority of the blacks are Asian professionals or business people – many of whom came relatively recently from East Africa.

The south and east of Brent (formerly the London Borough of Willesden) is, socially, completely different. It has some of the worst in-dices of deprivation in the whole country. Here, the housing stock is very old and often overcrowded; its residents are skilled of unskilled workers – many of whom are now unemployed. In the southern and eastern wards are concentrated the poorer blacks, most of whom are working-class and the majority Afro-Caribbean.

The councillors who now hold power in Brent have had the experience of living in the more deprived areas of the borough. In May 1986, Labour won forty-three seats; eighteen black councillors were elected – eight of whom were black women. These are not machine politicians, borrowing a line from time-worn institutionalised politics. They are, in the main, committed local who have themselves been at the butt-end of local government ineptitude, indifference and racism. Their political impetus comes from the simple wish to change things for their own children.

Hence the local education authority’s genuine concern about the underachievement of black children in its schools. The dissatisfaction amongst parents (especially Afro-Caribbeans) about education is no secret. The independent investigation into Brent’s secondary schools[1] (commissioned by a Tory-controlled council) bears this out, as does the recent report by HM Inspectors.[2] Though over half the schools’ children are black, until very recently only 10 per cent of teachers were. One way of helping black children to gain confidence in themselves and in their schooling is by employing more black teachers. And so Brent embarked on an ambitious recruitment drive for black teachers who were to be deployed throughout the whole borough.

In Sudbury, the ward in which Ms McGoldrick is headteacher (and which is solidly Tory), it was the belief amongst the middle-class parents – black and white – that white teachers would, ipso facto, mean higher standards and better educations for their children. The ‘Wembley mentality’ and the ‘colonial mentality’ were in agreement. Having a black skin – as a governor, as a parent of as a teacher – did not necessarily mean siding with the borough’s most oppressed, or caring about the underachievement of the majority. That many black parents, teachers and governors went over to Ms McGoldrick’s ‘cause’ reflected, instead, their preoccupation with maintaining ‘standards’. Or, to put it differently, blacks and whites were united in their attempt to uphold a common class interest.

Even if the idea of a borough-wide campaign to raise standards and find teachers with whom children could relate did not appeal to certain ‘better-off’ schools, it should have appealed to the union which represented Brent teachers. Schools were chronically short of staff. But it was in fact the union, represented locally by the Brent Teachers’ Association, which intensified all the contradictions between the teachers and the education authority. Not only did it refuse to cooperate with intensified all the contradictions between the teachers and the education authority. Not only did it refuse to cooperate with the independent investigation, it also withdrew its earlier support for the provision of the specialist advisory posts, once the commitment was made to appoint black teachers (on the grounds that it had not been consulted). A black teacher who questioned the union’s commitment to anti-racism has, allegedly, been threatened with disciplinary proceedings. Effectively, the union rubbished the council’s policies and, in the course of a series of legal actions, tended to portray its members as victims of black, racist, loony-left councillors. The union’s only concern, it appeared, was to maintain the power and conditions of its professional members – and they, of course, happened to be mainly white, middle-class and conservative in outlook. The union, is protecting the professional interests of its members was, in fact, perpetuating educational privilege.

Brent has been variously accused by its critical supports of bad public relations, of trying to do things too fast, or of choosing the wrong cases over which to fight. But such notions do not help us to learn perhaps for another time and another fight – the real and serious mistakes Brent’s Labour Council made, not in combating racism, but in the way it chose to do it. For, though it intended to fight racism and thereby enlarge socialism by using perspectives derived from the racial deprivation and discrimination experienced by the new working class perspectives consistently ignored by the Labour Party – the way the policy was carried out was confused.

The fundamental error was to take up an ‘anti-racism’ package for want of properly thought-out policies tailored to local needs. Such a package had originally been cobbled together by Labour authorities (and especially the Greater London Council) as an institutional response to the ‘riots’ of 1981 and to Lord Scarman’s discovery of ‘racial disadvantage’ and ‘ethnic need’. Such ‘anti-racism’ made no distinction between individual racism and institutional racism, between personal power and institutional power, and opened the door to all kinds of ‘skin politics’ and white ‘guilt-tripping’. It was the adoption of such a slick package and the implementation of its idea by officers that allowed the Council’s fight over policies to appear as a personalised vendetta against a few teachers. It was also why its fight ended up as a fight about the right to employ black teachers rather than as a fight for improving the education of all children, in which black teachers were to be the means to an end.

And it was inevitable that a minister in the Tory government so devoted to extending privatisation, to maintaining elitism and to destroying local government power would intervene in Brent to preserve ‘individual freedom’. But the fact that the Labour Party leadership was also prepared, in the run-up to a general election, to nail its colours to the same mast (and demand that its Brent members play down the fight for their educational policies) needs to be examined.

Brent’s education authority was, despite some error in tactics, fighting for very basic socialist principles. The fight between central and local government was not about racism versus anti-racism but about elitism versus democracy. Brent was trying to extend equality of opportunity to all its children and wished most of all to meet the needs of the borough’s most deprived. The idea was to raise up the lowest parts of the borough to meet the standards of the highest. The already – advantaged areas and schools, which sensed that their privilege was somehow at stake, declared war on such policies. The same battle had been fought twenty years ago by the ‘privileged’ grammar school sector against Labour’s comprehensive plans. But the Labour Party of today could not see Brent’s struggle as part of that same policy to democratise education.

Or, to put it another way, the struggle for a socialist education system in Brent was mediated through the struggle against racism – and therefore stood for greater justice. It was a struggle which should have opened out the Labour Party and the rest of the Left to the fact that this was a socialist battle. It should have shown in everyday practice how black struggle – for human dignity and true freedom – far from being divisive of, or in competition with, socialism, actually lies within and advances its best traditions. But the Labour Party, having drifted so far from its own tents and having failed, because of its own racism, to be informed by the socialist perspectives that the black working class had brought to it, was prepared to look no further than the Tory version or what was happening in Brent. Unable to fight as a party to clarify the politics of Brent and drive home to the nation the common denominators in the fight against racism and the fight for socialism, Labour sold out on itself.

[1] Jocelyn Barrow (Chair), Th two kingdoms: standards and concerns: parents and schools: independent investigation into secondary schools in Brent, 1981-84 (1986).

[2] Department of Education and Science report by HM Inspectors, Educational provi-sion in the outer London Borough of Brent (1987)