Editorial in Race Today, August 1973

Britain, as George Lamming once remarked, is a blotting paper society. It absorbs and dissipates discontent, dissidence, revolt; it even puts them to profit.

Trade unions, once an instrument of class struggle, have, in the course of achieving legitimacy, come to act as a buffer be tween the classes – absorbing the impact of working class radi calism on behalf of capital in exchange for wage concessions on behalf of labour. So crucial in fact is their role as stabilizers of the system that today they are a force in their own right, institutions of the capitalist state charged with the task of disciplining and policing workers who step out of agreed lines of realistic negotiation – negotiation, that is, which calls the system into question.

The purpose of trade union struggle, however, is to do ex- actly that: to call capitalism into question – to alter the owner ship of the means of production. The initial step towards that end is the organisation of the workers around demands that impinge on their every day consciousness: the price of their labour. But purely economic demands serve only to stem the encroachment of capital. They are, as Marx has said, efforts at maintaining the given value of labour – at retarding the down ward movement, but not changing its direction.

Nevertheless, it is through economic struggle, struggle with the effects of exploitation, that the working class attains to political struggle, struggle with the causes of exploitation. Only through the struggle for bettering one’s condition within the capitalist framework does one achieve the political consciousness to end capitalist exploitation altogether.

But it is precisely such a transformation that trade unions have failed to engender. And that failure does not stem merely from the sheer economism of their outlook (which, in any case, is an aspect of trade union struggle) but from the deliberate alliance of their politics with the reformist politics of the Labour Party. In the event they have blunted the edge of working class political consciousness.

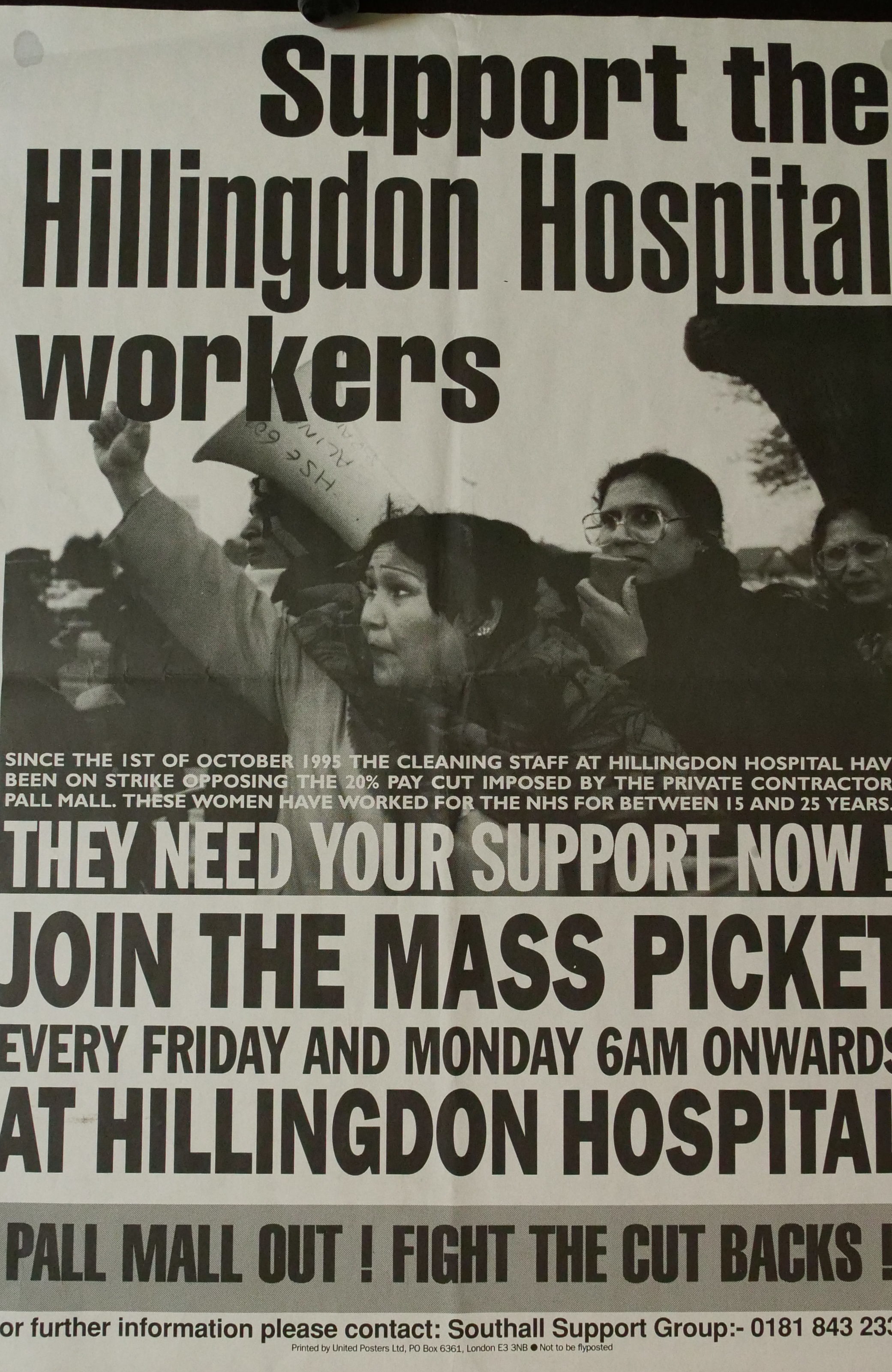

Black workers, on the other hand, have been forced, by the racist ethos of British society (worker and capitalist alike), to address themselves more directly to the political dimensions of their economic exploitation. They have, by virtue of the fact that their experience of economic exploitation is hardly separable from their experience of racial oppression, been compelled to recognise that a purely quantitative approach to the improvement of their conditions can by itself have no bearing on the quality of their lives. Their economic struggle is at once a political struggle. And that puts them in the vanguard of working class struggle.

To require them to join the trade union movement, there fore, is to ask them to abnegate their political consciousness and to play down their political role. Instead, it is up to the white workers to expel ‘the labour lieutenants of capitalism’ from their ranks while at the same time fighting racialism among the rank and file. The black workers for their part must organise separately, in any way they think fit, and leave it to the white workers, in a spirit of self-criticism, to defend such organisations.

It must be borne in mind, however, that even as capitalism internationalizes, the urgency for the working class to inter nationalize becomes more acute. The opportunity for such internationalisation – for reducing the concept of three worlds into its basic components of capital and labour – obtains here in the metropolitan country. But that unity must be real and organic, based on a common consciousness of class exploitation, not on dogma. And for that we must ‘put politics in command’.