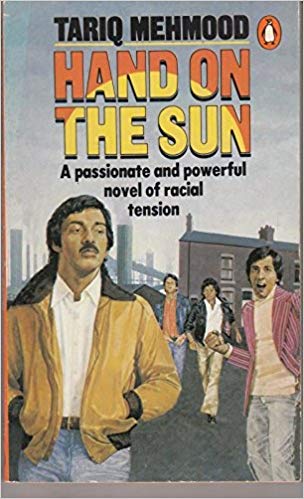

By TARIQ MEHMOOD (Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1983). 156pp.

This is the first authentic novel of the Asian experience in Britain – written in the taut, tense style in which that experience itself is lived in the interstices of a racist society. Inevitably it is a novel written by someone who – from his arrival here as a boy of eleven from a Pakistani village to his arraignment as a conspirator against the British state at twenty-five – has had his life forged on the smithy of his race, but, unlike Daedalus, finds therein the conscience of his class. And here, in the story of Jalib and his friends, the author charts the political journey of black youth in Britain.

Jalib’s father is a mill-hand, like most of the adult Asian population of Bradford, forced out of Pakistan by poverty and brought to Britain with tales of the gold of its streets. He had hoped to go back to his wife and children when the gold of his labour was won. But there had been no gold, just ceaseless labour – made more ceaseless still by the grow ing fear that he would be parted from his family for ever if he did not earn enough soon enough to get them over before the gates of Immigration closed on them. By the time they join him, he has become a joyless man, his life all ‘melted into the machines at the mill.’ He had exchanged one poverty for another.

Jalib’s history, however, begins in Britain. Of course, he too had dreamt as a boy of going to Wa/lait and one day becoming a white man. But the one thing he learns from the moment of his arrival – and at school – is that he is a wog and a Paki and fit only for being set upon by gangs of cowardly whites backed up by racist teachers, heads and policemen. And it is a lesson that is repeated over and over again throughout his young life – in the dole queue, on the streets, in the ‘illegal immigrant’ raid on his house for his cousin, in the arrogant marches of fascist parties through black areas – and in the lives of his family and friends.

Racism is the only experience that Jalib has or is allowed to have. It is his over-riding consciousness. Even his love for Shaheen, though conducted to the tune of his culture, is distorted by the tempo of racism. And it is only through his struggle against racism, his struggle for another reality, that Jalib gains a deeper understanding of duty and comradeship and love. Only through defending himself and his friends against racist attacks does he appreciate the value of comradeship. Only through defending their community against the incursions of the National Front do Jalib and his comrades understand the quality of duty. Only in the heat of struggle do they learn to honour Dalair Singh, the veteran of many battles against the British Raj, and arrive at an understanding of the continuum of struggle and learn to ‘make our history into a weapon’. And only, finally, through successfully mobilising their community against Ghulam’s deportation (ostensibly as an ‘illegal’ but in reality to break the strike he was mounting at the mill) do Jalib and his friends come to understand that their struggle must be rooted in the people, uniting the many, isolating the few – refusing to be waylaid by ‘revolutionary socialists’ or reformist elders– working out in the process the dynamics of race and class and culture. But in the moment of their victory, Jalib also learns of the cooption and corruption that await a successful leadership.

Shaheen, too, is formed in the crucible of her people’s struggle against racism. When she first baulks at an arranged marriage to her cousin in Pakistan, it is because she wants to be free to choose when and whom she marries and because she has seen how in Britain traditional marriages had locked up women like her mother and Jalib’s mother within the four walls of their homes and left them prey to loneliness and despair. (They were afraid to go out and missed the company of women with whom they could ‘sit and talk, laugh and joke, plot and plan’.) And yet she cannot run away: she owes her parents a duty and her younger brothers and sisters a guiding hand. But her personal problems begin to fade when little Malkit is savaged by skinheads and she determines to join the fight against them. ‘It’s no bloody good just eating ourselves up when these skinheads, coppers and others are doing so much wrong to our folk.’ She had earlier ‘seen her problem in isolation; now she was beginning to see it in relation to other people’. And through that she arrives at a higher duty, a duty to her people, a political duty and a resolution to her problem. She owes it to Maqsood to marry him so as to gain him entry into Britain, but she owes it to herself not to stay married.

It is unimportant that the author appears to make no conscious effort to weave the strands of his story together – or give it ‘plot’ or develop ‘character’. He tells his story simply, truthfully, directly – in the oral tradition of the story-tellers of the Indian subcontinent, in the tradition of the Panchatantra.