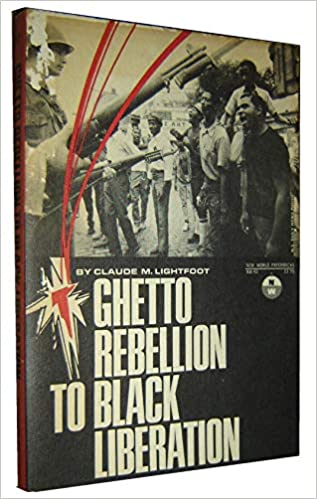

Ghetto Rebellion to Black Liberation byClaude .M Lightfoot (International Publishers, 18s 6d., 192pp)

Claude Lightfoot is one of the Communist Party’s old faithfuls. He joined the party in 1931, after a brief affair with Garveyism, and has remained true the the party line ever since-despite the vicissitudes of the McCarthy era (he was arraigned under the Smith Act) and the continuing failure of the CP to harness effective works’ support for the Negro cause. It is inevitable, therefore, that Ghetto rebellion to black liberation should portray the strength and weaknesses of doctrinaire communism: a probing diagnosis of Negro ills coupled with a wishful, starry-eyed prognosis that a black/white workers’ coalition will reclaim America and the Negro.

Racism, argues Lightfoot, is only a symptom of the deeper malaise; the disease is capitalism and, since world war two, monopoly capitalism. The industrial-military complex, which took over the American economy during the war years, continues to determine the country’s affairs, resulting in imperialist aggression abroad and fascist repression at home.

So pervasive is the “invisible government” in the nation’s policies that the most powerful executive in the (democratic) world has become no more than a figurehead, no less than a fall-guy. For the country’s economy, the consequences have been disastrous. Recurring unemployment is not merely on the increase, but has become a matter of policy, naked and unashamed. Over 80 million of the nation’s ponpulation live below the poverty line. Congestion in housing, schools, social amenities, etc., has reached such nightmare proportions that mental illness, crime and air and water pollution have come to be accepted as commonplace. The affluence of the workers is more apparent than real: not merely their possessions but even their lives are in hook. And advanced technology itself has become a curse: “it does not ease the burden of the worker it eases him out of a job.”

40 years on from the sixth world congress of the Communist International, and the party line on the “Negro question” has not altered in the slightest. The dialectical draftsmen of the Kremlin continue to sit at their drawing-boards, perfecting their blueprint for revolution, even as the coloured peoples of the world have begun to believe that the ideology of racism has overtaken the class struggle. To be white is to be a class above the blacks: the psychological superiority of colour masks the economic relatedness of class. Besides, the American Negro can no longer await “the objective situation”. He cannot contribute to the Communist Party’s philosophy that there is a time for reform and a time for revolution.

Reforms, if they come his way, must be engendered of his revolutionary struggle. So too will the consciousness of the workers or of any other cross-section of the white society be created. But all these are incidental to the main purpose, which, in the words of Carmichael and Hamilton (in Black Power: The politics of liberation in America, Cape, 1968) is that black people must . . . become their own men and women-in this hour and on this land by whatever mens necessary”