The Speech to the Azanian People’s Organisation Congress ‘Defend the people, resist neo-colonialism – advance socialism’, 22 December 1990, Langa, Cape Town; Race & Class, 33/2, October 1991)

Comrades, friends, comrade president, brothers and sisters. I am honoured that you should ask me to come and join you in your deliberations today, at this your tenth and perhaps most momentous Congress.

I am particularly honoured that you should ask me now, at this time, when Azania is at the cross-roads of history- at a time when you are embarking on one of the most unique experiments in human endeavour: to create one Azania, one nation out of so many different groups and peoples and nationalities – and that at a time when nation states are breaking down into ethnic and national entities all over Europe and the USSR. It is as great an experiment as the Bolshevik revolution. Only, this time we cannot fail. For, unlike the Bolshevik revolution, this is a revolution that is rooted in humanity, in what it means to be human. It is not just an economic experiment, an economic project which, if gotten right, would put everything else in society right. It is not a project that believes that, in getting rid of class inequality, we will have got rid of racial and sexual inequalities. On the contrary. Our project stems from the belief that all inequalities – whether of race, class or gender – are symbiotic of each other, live off each other and are sustained by each other. And not to wipe them all off in one fell swoop is no project at all, no revolution at all.

For if, as Du Bois pointed out in 1903, ‘the problem of the twentieth

…. —

century is the problem of the colour line’, then today, at the end of the century, it is blindingly clear that the colour line is the power line is the poverty line. Our business is to end that equation between race and poverty and powerlessness, to remove the degradation which makes race the arbiter not just of one’s place in society, but of one’s whole life, of how it is lived and where and when – and at whose behest. And nowhere is that equation between race and class and power more entrenched than in South Africa. In South Africa, one might even say, race is class and class race, and the race struggle is the class struggle.

Or let me put it this way. The fight against racism is, in the first instance, a fight against injustice, inequality, freedom for some and un-freedom for others. But because that racism is inextricably woven into the hierarchies of power and, in some instances, as in South Africa, determines those hierarchies of power, the fight against racism, in the final analysis, is also a fight against an exploitative system.

And who else is better fitted to carry out that fight than you, the comrades of Azapo, the brothers and sisters of the Black Conscious ness Movement? Who better to understand that the struggle for black worth, black dignity, black freedom is also a struggle that uplifts the quality of life for all – is a struggle for socialism?

It is that understanding of Black as a political colour, of black struggle as a struggle for socialism, that connects me directly to you and brings me here today. Not just because we too in Britain have suffered discrimination on the basis of our colour. Of course, it is nothing compared to yours. Not even because we too in Britain have had our deaths in custody, our unjust sentencing, our police harass ment, our violence on the streets. And, of course, they are nothing compared to yours. But because in our fight against that racism, in our fight against the human waste that racism created in our communities, we too, the so-called ethnics of Britain -Afro-Caribbeans, Asians and Africans- banded together, in the 1960s and the 1970s, on the factory floor and in the community, as a people and a class and as a people for a class. Uniquely, as nowhere else in the western world, we forged a unity based on our common colonial history, our common fight against racism, and our common status as working people (the vast majority of us were working class at the time). And Black was no longer the colour of one’s skin, but the colour of one’s politics.

Nor did we allow our politics to be contaminated by white liberals or the white Left. Too often in the past we had listened to our white comrades, followed their theories and their strategies, and lost control over our own destiny, the authority over our own experience. Our fight, we told them – as blacks – was from outside the system, from outside the monster; theirs as whites was from within the system, within the belly of the whale. Both fights militated towards the same end, but each was determined by its particular history, and to confuse

the two would not be just to weaken the battle but to lend ourselves to defeat yet again.

But white people are stupid, you know. They arc so bound up with themselves and their own importance that they do not understand simple things. So we told them that there are two ways of fighting the same enemy. One is for you to come over to my side and help me beat him up- but, in the process, you’ll tell me what do do and how to do it and once again remove my authority over myself. The other is for you, who knows him so much better, to hold him, weaken him (from within, so to speak) so that I can beat the shit out of him. That way we achieve the same end without forgoing our different histories, that way we make the conditions to make a common history together in the future. To enter into an equal relationship now, before we are equal, would only help to make us unequal once more, unequal in the struggle for equality.

Those were some of the things that the black struggle in Britain had in common with the Black Consciousness Movement. But there were other resonances too, such as the time when Afro-Caribbean youth at the Notting Hill carnival in August 1976, inflamed by police harass ment, burst into riot and, setting fire to police cars, shouted ‘Soweto, Soweto·. The sounds of the struggle of the youth in your townships had reached the cars of the youth in our inner cities.

To turn to the theme of the Congress: Defend the people, resist neo-colonialism. advance socialism.

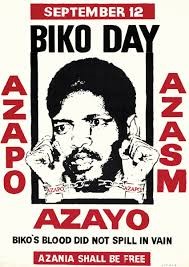

Defend the people. Where else could I go for my text but to Steve Biko? For there is no one I know of, in these times, even in this country, for whom defending the people was so central to his belief. the guide to his action.

You know better than I do of all the ways that Comrade Biko defended the people. I just want to remark on two which appear to me to be both timely and necessary.

In the first place. Steve Biko did not just speak for his people. His voice is the voice of the people – free of jargon. free of intellectual isms. free of the scleroscd language of the white Left, a language which had frozen ideas into slogans. dogmas, creeds, hymns, till no one could think for himself or herself afresh. The thinking was already in the language. The thinking came from the top and was encapsulated in the language and was handed around like capsules, handed down like tablets.

Comrade Biko roots his thinking in ordinary life, in everyday perceptions common to all, in common experience. and contextualises that experience in society, in the order of things – and shows by his actions, his practice, that in order to change that experience, we need to change society, change the order of things. He goes directly from the experience to the conceptualisation of experience to the changing

of experience. Experiencing and thinking and doing, for him, form a continuum, an organic whole. If you want to know the taste of a pear, he might have said with the Chinese, you must change its reality by eating it.

And because experience, for him – and this is my second point – was all experience, at all levels of living, he finds worth too in the small, everyday, mundane things that people affect or are affected by

– like the songs they sing to themselves, on the streets, at work, like the unadorned, unsolicited visits they make to each other’s homes, like the conversations they have on the street corner, like the spontaneous joy they give themselves up to in meeting others, breaking out in collective song and dance – in celebrating what he calls Man.

He speaks of African culture as going with the grain of nature, not against it; property as community-based, belonging to the people collectively; poverty as foreign to the African way of life, Africans share; religion as part of everyday activity, a continuing part of life. ‘The great powers of the world’, he once said, ‘may have done wonders in giving the world an industrial and military outlook, but the great gift still has to come from Africa: giving the world a more human face.’

For him, the cultural, the political, the social, the economic, the spiritual were all one, all material; they were all attributes and manifestations of Man; they were all to be experienced and under stood and used – to fuel and fire the struggle for change or to be discarded as irrelevant, old-fashioned, dated, treacherous, if obstruct ing that struggle.

But capitalism fragments us, divides us within ourselves. Colonial ism uproots us, separates us from our people. Neo-colonialism plunders us, robs us of our resources.

If we are going to combat neo-colonialism, however, combat imperialism, we must understand the way it works today- because we have moved from an industrial era to a technological era, with computers and robots and lasers allowing Capital to set up mobile global factories stretching from Silicon Valley in California and Silicon Glen in Scotland to the Free Trade Zones of Sri Lanka and Singapore, allowing Capital to move from one cheap pool of Third World labour to another, extracting maximum profit from each, and discarding each when done.

Capital has broken its national bounds and has become multi national – and the governments of Europe and America must follow the economic diktats of multinational corporations to set up the social and political order in Africa and Asia and Latin America that best serves the interests of big business. And, if western governments are the political agencies of multinational capital, the IMF and the World

Bank are the economic agencies that prepare the way for foreign investment and piracy.

Don’t for a moment believe that Mr De Klerk is dismantling apartheid to accommodate your rights and improve your welfare. He doesn’t give a damn about your rights and your welfare. He is doing it because the multinational corporations have told him, through their political agents, the western governments, to create a climate fit for investment, that he had better give the blacks a few rights so that they don’t go upsetting the apple cart. And that is why now, with a shake of the system here and a shake of the system there, they think that they have managed to bamboozle the blacks into thinking the climate is changing, and sanctions can be lifted. And black parties are being urged to buy into this system of all things, into the capitalist system, the free enterprise system, the dog-eat-dog system, the system that has systematically enslaved and degraded us.

There is no freedom for black people this side of socialism. That is

our birthright, that is our tradition, that is where we come from – from that sense of community, of camaraderie, of good neighbourliness – where the individual good comes from the collective good, and the individual is nothing and the community everything.

And there is no little-by-little socialism. You can’t be a little bit socialist like you can’t be a little bit pregnant.

And you can’t negotiate your way into socialism. Those who have, do not give; those who haven’t, must take.

And you can’t have socialism after liberation, because that way socialism never comes. Those who take power on behalf of the people do not give it back to the people. See what happened in the Soviet Union.

No, we must be socialists now, on the way to liberation. Our organisations, our structures, our way of working, our own personal growth must be socialist now, on the way to liberation.

There is no socialism after liberation, socialism is the process through which liberation is won.

Amandla!