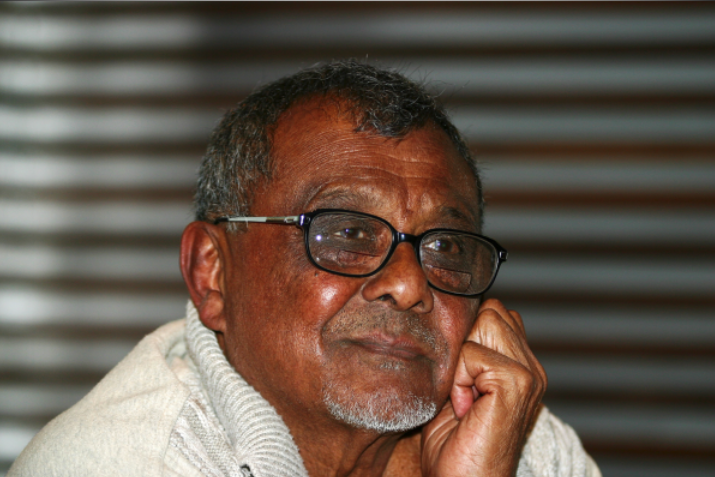

A.Sivanandan was one of the most important and influential black thinkers in the UK, changing many of the orthodoxies on ‘race’, heading the Institute of Race Relations for almost forty years, founding the journal Race & Class, and writing the award-winning novel, When Memory Dies, on his native Sri Lanka.

A.Sivanandan 1923-2018

A.Sivanandan was one of the most important and influential black thinkers in the UK, changing many of the orthodoxies on ‘race’, heading the Institute of Race Relations for almost forty years, founding the journal Race & Class, and writing the award-winning novel, When Memory Dies, on his native Sri Lanka.

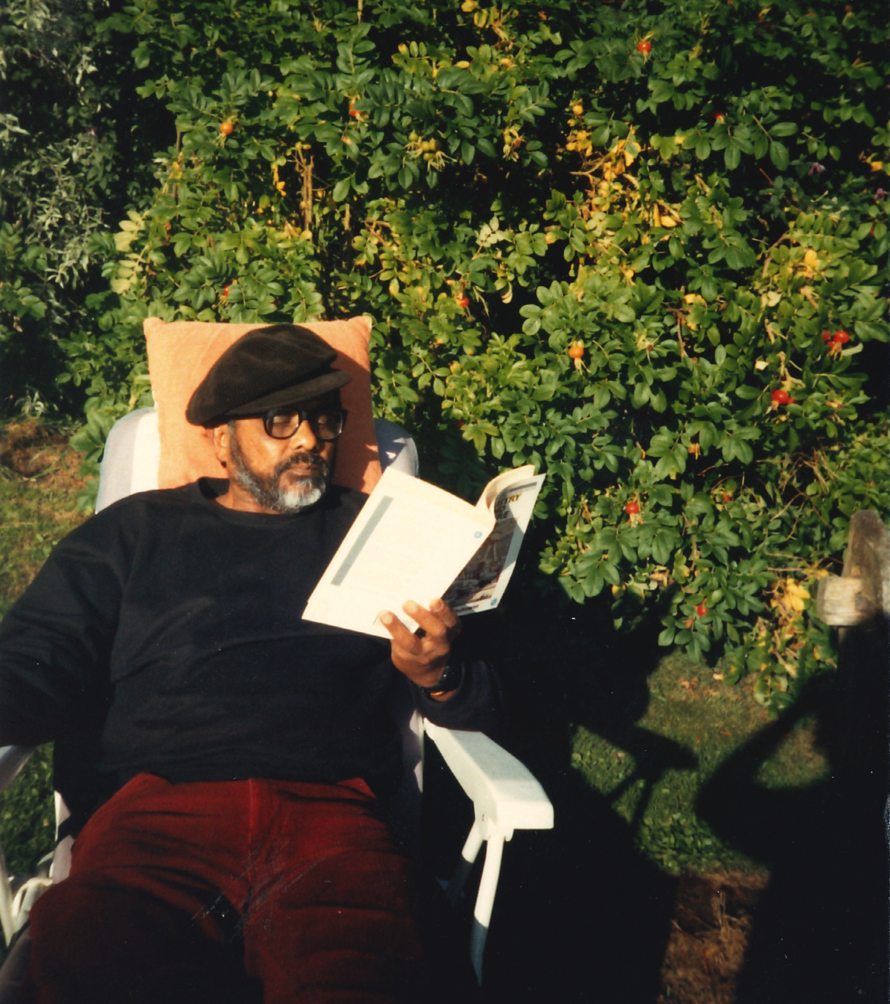

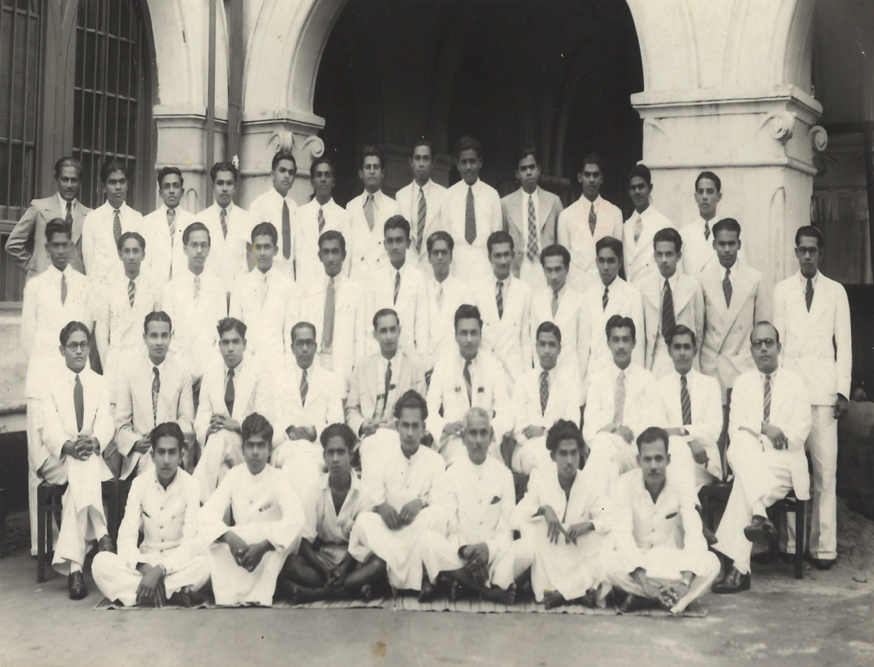

Younger days

Sivanandan (Siva) was born on 20 December 1923 in Colombo, the capital of Ceylon, then a British colony. His postal clerkfatherAmbalavaner and mother Nageswari both came from the village of Sandilipay in Jaffna in the north of the island. As his father was frequently moved around the country from post office to post office, Siva, the eldest son, was boarded with relatives in Colombo so as to have continuity in his education, though his summers were spent with his family in Sandilipay.

His senior education was at the prestigious but strict and Catholic school St Joseph’s College, Colombo (Siva, a Tamil, had been brought up as a Hindu.) He later studied at the University of Ceylon graduating (with a Third-Class degree) in Economics in 1945. University was where he first came across left-wing teachers (many from the LSE) and also where he became a fellow traveller of the Trotskyist Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP).

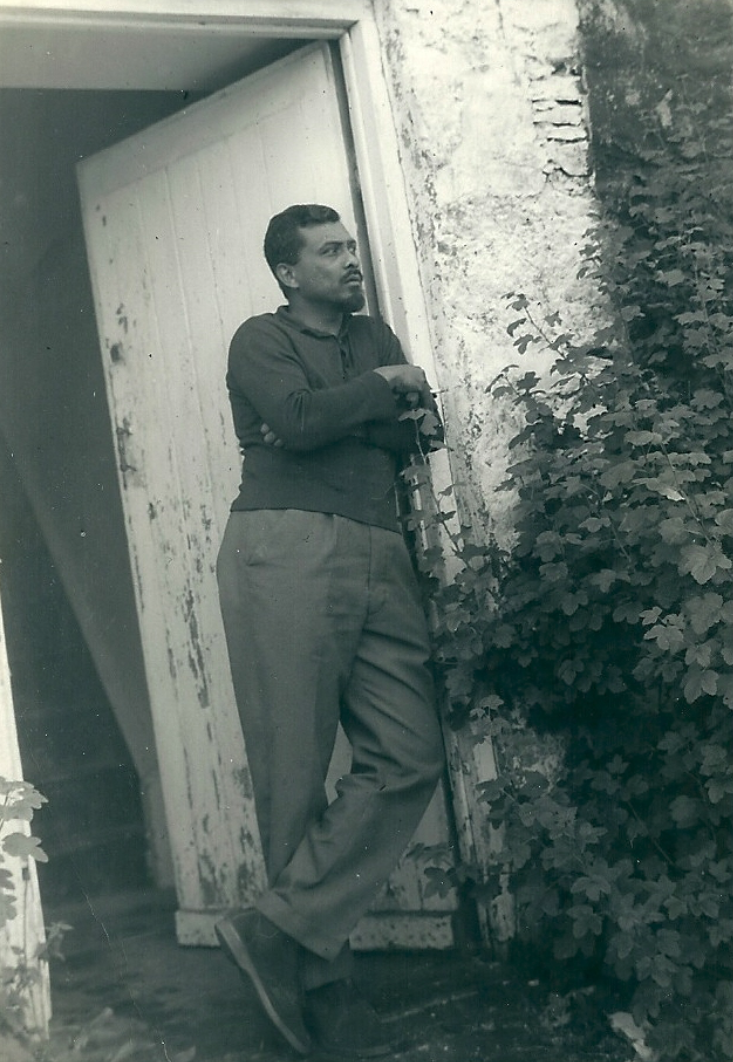

He first went to teach in the Ceylon ‘Hill Country’, i.e. tea plantation area, and then, from 1948, because of family pressure that he follow a well-paid profession that would help provide for the poorer extended family, he entered the Bank of Ceylon (BoC) as a staff officer and later became one of the first ‘native’ bank managers – though he had frequent run-ins with the British management and also played a part in forming the first trade union in the bank. From a chance meeting with an Austrian trade minister at the bank, he was invited on a scholarship to the Osterreicher Lander Bank in Vienna. It was on this first extensive trip to Europe in 1953 that he became familiar with western classical music and the European art, architecture and ambience, which till then had just been part of his imagination fired by the reading of British poetry and fiction and the songs and hymns taught by Irish priests.

Moving to the Mother Country

In 1950, Siva, Tamil and Hindu, married a Christian Sinhalese younger woman in a ‘love match’. This kind of mixed marriage was initially frowned upon by both families. And, after the communal riots of 1958 in which the Tamil minority was attacked and he had to rescue his own relatives from screaming mobs, he began to realise how hard it would be to bring up his three children in that hostile atmosphere.

He left for Britain to find a job and place for his family to live. And the place he found to rent was in Notting Hill – itself in the summer of 1958 the place of anti-black rioting. (His feelings on bringing his family to the UK in 1958 are summed up in his short story ‘The Homecoming’ in Where the Dance is.)

Becoming a librarian

Getting a job in banking commensurate with his qualifications was out of the question. Banks did not hire ‘coloured people’ especially in positions of trust where they would be in contact with white people. He ended up as a temporary clerk in Vavasseur and Co (a company he had traded with as manager in BoC) and decided he should, given his love of literature, retrain as a librarian. Sivanandan took a job in Middlesex libraries and worked variously in public libraries, for the Colonial Office library and in 1964 was appointed chief librarian at the Institute of Race Relations (IRR) in central London.

He was one of the first black librarians in the UK and found himself in the creation of the IRR’s unique collection also having to devise a new classification scheme that spoke to the racism and colonialism within the way in which ‘race’ was being studied. He was to act as advisor to a number of other collections in the UK and USA and created in the late 1960s bibliographies and registers of research for the IRR. The library which developed an information service became the main centre in the UK for the monitoring of the daily national and regional press on all matters relating to ‘race’. In its heyday this library service had seven members of staff working on its collection of cuttings, hundreds of journals, pamphlets and book collections on race relations across the globe. During the late 1960s and early 1970s the IRR’s library became an important conduit for radical Black Power material from the US and anti-Colonial material from Africa reaching some of the burgeoning black groups in the UK. It was opened in the evenings for members of black organisations to access some of the latest writings. The library on race relations built up by Sivanandan was, in 2006, moved to the University of Warwick Library, where it is known as the Sivanandan Collection. Materials on early black settlement and black struggle have been retained at IRR and catalogued as the Black History Collection.

Becoming a writer and speaker

It was from 1967/68 onwards that the influence on Siva of the US’ Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, and in the UK of racist immigration laws, Powell and the limitations of CARD (the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination) and liberalism in the face of racism, became apparent. He began to review new ‘black’ publications (from Fanon to Baldwin and Cabral) comment on happenings and speak publicly on ‘race relations’. He visited the US in 1968 where he met with members of the Panthers and he was instrumental in helping develop the World Council of Churches’ radical Programme to Combat Racism in 1969. When the IRR’s Newsletter changed in 1969 to Race Today he helped to provide its more critical edge and frequently wrote for the new magazine – his pieces often being reproduced in black community papers such as Black Voice and Tricontinental Outpost, in Liberator in the US, and, later, in Asian grassroots newsletters.

All change at the Institute of Race Relations

The IRR, which Siva joined in 1964 as chief librarian, was a product of Empire, founded as it was in 1958 by a former member of the Indian Civil Service and had a board of management reflecting the interests of some of the largest international companies, media outlets and members of the Houses of Parliament. ‘Race relations’ was perceived as something elsewhere and, if, at home, something to be discussed dispassionately by those who knew best. The dominant ideas of the time were of the need for assimilation and later integration – that is of the New Commonwealth immigrants.

The ideas that the new settlers might not be the problem, but a racist society, that the settlers themselves should have a voice in defining and acting against racism were quite revolutionary. The management board was completely out of touch with such views and its members surprised to find their attempts, to muzzle staff critics of policy-oriented research and sack the editor of Race Today for being partisan over Apartheid, met by consolidated opposition from staff and the IRR Membership which had been principally organised by Sivanandan. (This can be read in his ‘Race and Resistance: the IRR story’ Race & Class 50/2 2008)

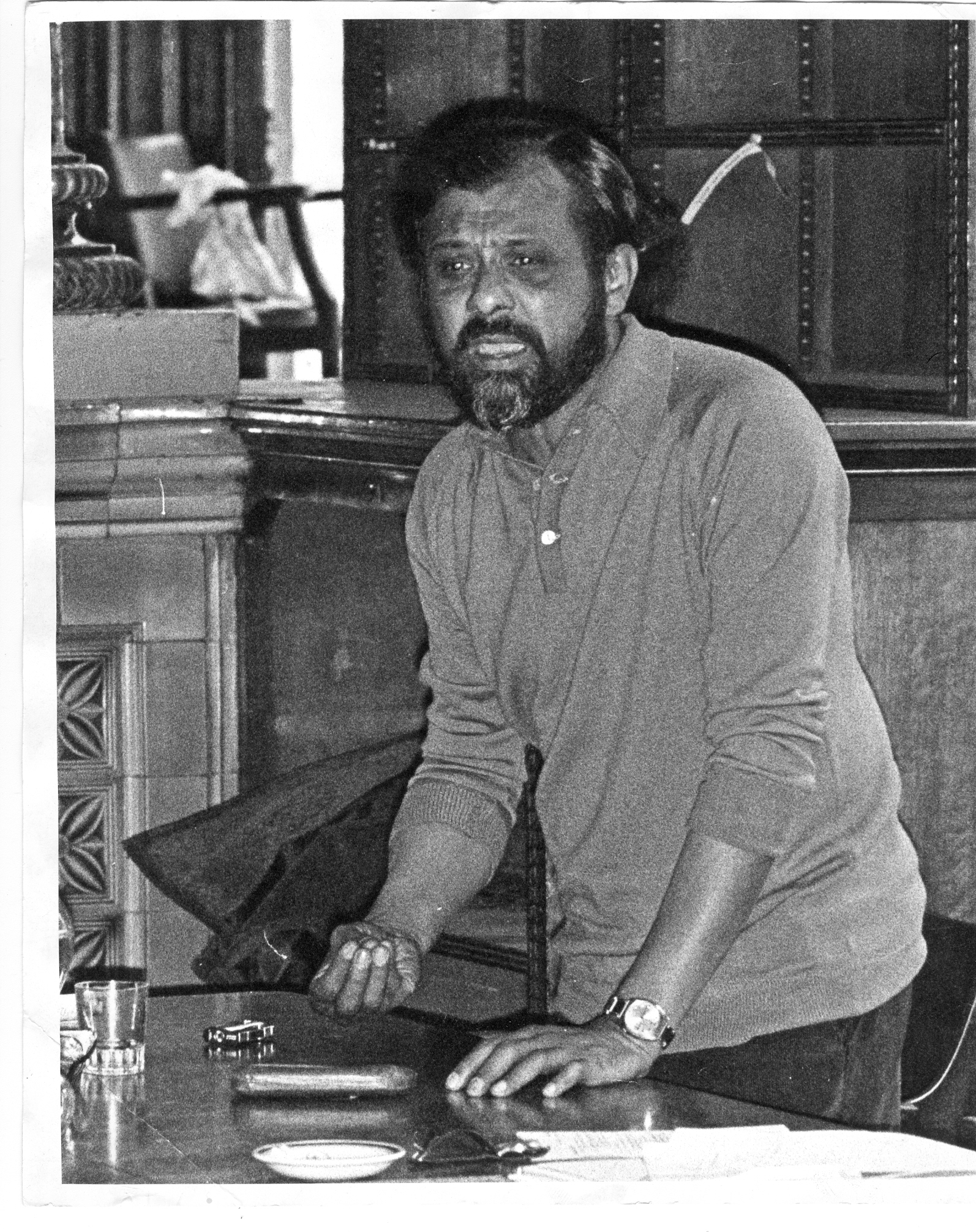

In April 1972, following an internal struggle at the IRR with staff and members on one side and the Management Board on the other, over the type of research the IRR should undertake and the freedom of expression and criticism staff could enjoy, the majority of Board members were forced to resign and the IRR was reoriented, away from advising government and towards servicing community organisations and victims of racism. Sivanandan (head of library services) was encouraged by the staff to become a joint director with Simon Abbott (assistant director and head of publishing) and later as from late 1973 Siva became sole director, a post he held till 2013.

The IRR had been housed by the old guard in a number of rented buildings around Piccadilly in London’s Mayfair, but moved in 1974 to Pentonville Road, London N1 and in 1984 to Leeke Street, off Kings Cross Road, London WC1.

New beginnings

Under Sivanandan’s directorship the IRR began to change tack from speaking to the powerful to speaking from the powerless. It broke with long-term empirical research, now producing short-term research, based on case studies, with results published in accessible ways as pamphlets that could be used to intervene in struggles against injustice in areas not popularised by academics – e.g. over policing, the rise of the National Front, school exclusions, community care, deaths in custody. Sivanandan’s IRR also spoke out against empty multicultural educational policies which emphasised cultural difference without addressing the racism of British society (see IRR’s evidence to the Swann Committee in 1979.). To meet the lack of provision of basic narratives, IRR produced a series of educational pamphlets for young people in the 1980s– Roots of racism, Patterns of racism, How racism came to Britain and the Fight against racism.

Retrieving Black British history, too, especially that made by post-war working-class settlers, was at the forefront of Siva’s vision. Following the 1981 uprisings he produced ‘From resistance to rebellion’ which was the history of the different struggles on the factory floor, the streets and communities and over different generations from the 1940s to 1981 – revealing that black working- class struggle was now part of British working-class history. After this, IRR produced a number of pamphlets on the history of local communities and four films, ‘Struggles for Black Community’ for Channel 4 TV directed by Colin Prescod.

The IRR under Siva was not standing on the side-lines of racial politics. And it was, with the increase in racist attacks and because of his belief that racism was the breeding ground of fascism, that the IRR first helped in the launch of Searchlight magazine during the early 1970s and then helped to sustain in 1977 the All London Anti-racist anti-fascist Coordinating Committee and its paper, later a magazine CARF. Between the 1970s and 1990s he spoke frequently to community groups such as Newham Monitoring Project and Southall Monitoring Group and BAME professionals — in education, housing, health, social work, librarianship, the arts, the churches — looking for radical ways of countering racism in their institutions.

From RACE to Race & Class

One of the hardest tasks facing the new IRR was to make its dry, academic quarterly journal RACE relevant to the new world emerging post-Vietnam, Black Power and socialist reconstructions in the Third World. In April 1974 Siva was appointed editor of the journal which was renamed in October 1974 Race & Class. In his first editorial, which indicated that a new editorial board was in the making, Sivanandan enunciated the principles of the journal: that we write in order to do, that the people we are fighting for are the people we are writing for. In other words, articles should be as accessible as possible and free of jargon, on the one hand, and on the other, include perspective as to how to bring about change.

Under his editorship, Race & Class – with the strapline ‘a journal for Black and Third World Liberation’ – became the leading international English-language journal on racism and imperialism, attracting to its editorial board Orlando Letelier, Eqbal Ahmad, Malcolm Caldwell, John Berger, Basil Davidson, Thomas Hodgkin, Jan Carew, Cedric Robinson, Colin Prescod, Manning Marable, and, later, Barbara Harlow, Neil Lazarus, Tim Brennan, Nancy Murray, Barbara Ransby, Chris Searle, amongst others. As from 2000, the journal, still under the editorial control of the IRR and now the line, ‘a journal on Racism, Empire and Globalisation’, has been published, marketed and distributed by Sage Publications, which has very much increased its visibility worldwide.

Established as a writer

Sivanandan’s writings and speeches, which spanned over four decades, covered a multitude of subjects – the black experience, migration, political struggle, technological change, globalisation, developments in Sri Lanka – but always with a race/class analysis. He did not consider himself a theoretician and also avoided calling himself a Marxist (since he said he was not at the barricades) but regarded his writings, often overthrowing orthodoxies, as important political interventions.

Much of his work was first published in the journal Race & Class. ‘Race, class and the state’ (1976) provided the first coherent class analysis of the black experience in Britain, examined the political economy of migration and coined the idea of state, structured racism. ‘The liberation of the black intellectual’ (1977) examined identity, struggle and engagement during decolonisation and Black Power. ‘From resistance to rebellion’ (1981) tells the story of black protest in the UK from 1940 to 1981. ‘RAT and the degradation of black struggle’ (1985) made the crucial distinction between personal racialism and institutional or state racism. He was in this piece and others such as ‘All that melts into air is solid: the hokum of “New Times”’(1990) highly critical of some trends in modern leftism, such as that of Marxism Today in the late 1980s, and of Postmodernism. ‘Race, terror and civil society’ (2006) showed new racisms, such as the attack on multiculturalism and growth of anti-Muslim racism, thrown up by globalisation post-9/11. Changes in productive forces, especially the technological revolution, were themes taken up in ‘Imperialism and disorganic development in the silicon age’ (1979) and ‘New circuits of imperialism’ (1989). One of his last interventions was on the impact of neoliberalism, ‘The market state vs the good society’ (2013).

On Sri Lanka

Though it was communalism that drove him out of his country, Ceylon, Siva was of the generation that had been brought up with, educated alongside and had many friends among the Sinhalese. Although he did, from the 1960s, write about the language issue in Ceylon, his political activism related in the early 1970s to countering growing repression by the state against the left and against plantation workers. Siva visited his native country as often as he could, contributing what he could by way of talks and workshops and in the UK by public education. He was a member of the UK-based Ceylon Committee which organised against the repression of the leftist Janatha Vimunkthi Peramuna, which had staged a coup in 1971; later in 1975 he drew attention in the UK Aid Sector to the destitution of former plantation workers at the hands of the Ceylon Coalition government. But it was witnessing again first-hand anti-Tamil riots in 1977 when he was in Colombo and meeting with members of new radical Tamil youth groups both in Jaffna and London in following years that led him to focus more on the Tamil question and Tamil rights. He edited the special issue of Race & Class: ‘Sri Lanka: racism and the authoritarian state’ (1984) in which he wrote on ‘Racism and the politics of underdevelopment’ and later ‘Sri Lanka and the Tamil struggle’ (2009). But his greatest contribution was the novel When Memory Dies (see below).

Book Collections, etc.

Sivanandan’s political non-fiction articles were published in a number of collections:

A Different Hunger: writings on black resistance, 1982 (Pluto Press);

Communities of Resistance: writings on black struggles for socialism, 1990 and 2019(Verso);

Catching History on the Wing: Race, Culture and Globalisation, 2008 (Pluto Press).

He also published an epic novel on Sri Lanka entitled When Memory Dies (Arcadia Books, 1997) which won the Commonwealth Writers’ First Book Prize (for Eurasia) and the Sagittarius Prize.

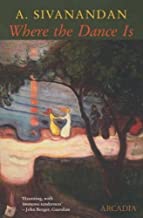

A collection of his short stories was published entitled Where the dance is (Arcadia Books, 2000).

A collection of his short stories was published entitled Where the dance is (Arcadia Books, 2000).

In the same year, Sivanandan collaborated with British band Asian Dub Foundation in their album Community Music, providing one of his treatises as lyrics for the track Colour Line, in which Sivanandan also providing some singing.

National Life Stories conducted an oral history interview (C464/76) with Ambalavaner Sivanandan in 2010 for its National Life Stories collection held by the British Library.

End but not ending …

Siva was in poor health for some years, though still contributing remotely to the IRR and the journal. He died at his home in Hertfordshire on 3 January 2018. A celebratory memorial event was held on 23 June 2018 at Conway Hall to discuss how to take his principles on into the future. To find out more about how he impacted on a range of people – from the grassroots to the ivory tower, and across continents – look at the tributes page http://www.irr.org.uk/news/a-sivanandan-1923-2018/ and also the longer essays produced in a special issue of Race & Class to mark his 75th birthday, ‘A world to win’, (41/1and2) July 1999.