Introduction to ‘Chris Searle: the great includer’ a special issue of Race & Class, 51/2, October 2009.

When I was a wild colonial boy growing up in Ceylon and attending a missionary school, everything I was taught was imbued with the idea of the Englishman as hero and exemplar – devoted to the betterment of the native peoples and to the task of teaching them to govern themselves. He was brave, but self-effacing. He was stern, but just. He was disciplined, but not irrational. He had feelings but did not show them – as evidenced in his upright carriage and his stiff upper lip. An officer and therefore a gentleman, brought up on the playing fields of Eton and Harrow, he was possessed of a sense of honour and a code of fair play – as embodied in the very game he played, and signified in the metaphor it threw up for unfair play: it’s not cricket.

In victory he was humble, in defeat magnanimous. He treated success and failure just the same. He was a good loser: never questioned the umpire or kicked an opponent when he was down. He cheered the under-dog even as he beat him.

That was the Englishman I was brought up on, not that I knew any in the flesh, removed as they were in the halls of power.

And then I came to England and found it all a myth: a set of attributes that did not exist in the real world, values that were only observed in the breach. Or it was a culture of mock heroism that turned out mimic Englishmen in the service of their own subjection. Where was the cricket in that?

Or so I thought till I came to know Chris Searle, all six-foot five of him – and every inch an Englishman. He, too, was on a mission, without being conscious of it – to teach, to learn, to learn as he taught – children, adults, communities – to serve, to bring out the best in people, to let them put forth, flower, grow to their full height – exhaust the limits of the possible. And always against the odds, against poverty and social dislocation, against entrenched power. He had all the insignia of the Englishman I was brought up on: the stiff upper lip, yes: he was shy. The loose lower one, no: he was no hypocrite. On the contrary. His love of ordinary people was so natural and his hatred of injustice so acute that his feelings showed not in outward sentiment towards the individual but in inward passion for the cause he fought.

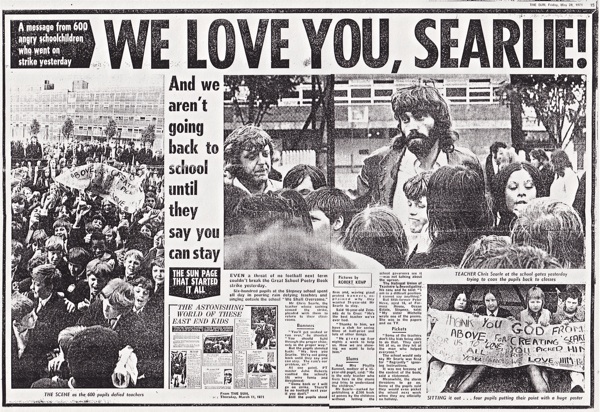

No mean cricketer himself (he once played for the England youth team), fair play came to him as of nature, in cricket as in life. Witness, for instance, his sacking from an English-teaching job in a Church of England secondary school in London’s East End (1971) for editing and publishing Stepney Words, a collection of poems he had encouraged his pupils to write to express their felt experiences and concerns – which the school governors found subversive of their authority. The students went on strike on behalf of their teacher. Chris persuaded them to go back: their interests were paramount. The students claimed that the governors were sacking Chris because the poems were anti-religious, whereas the governors maintained that the book was published ‘against their instruction’. Chris accepted that the governors had a point and their good faith could not be put in question. What was in question was the system, not the individuals.

Some twenty-five years later, Chris was sacked from the headship of Earl Marshal comprehensive school in inner-city Sheffield because he refused to ‘exclude’ ineducable children from school: children did not fail themselves, teachers failed them – especially immigrant children whom racism had already excluded from mainstream society. The authorities accused Chris of reducing Earl Marshal to a sink school, and it would have to be closed.

In both Stepney and Sheffield, Chris, like the mythical Englishman, triumphed against the odds: he was reinstated at John Cass and, though he stayed sacked from Earl Marshal, the school itself was never closed – and he had left them both open to the idea of the school in the community and the belief amongst students that ‘none but ourselves can free our minds’.

These, then, were the ideas, principles, values, forged on the smithy of struggle in the ghetto schools of England, that guided Chris and were in turn further developed when, betwixt times, he went to the newly emerging socialist countries of Mozambique and Grenada to teach school and help shape educational policies that went with the grain of their societies. From 1976–78, during Frelimo’s rule, in Mozambique – where poverty had decreed that children went to school (which they themselves had helped to build) in between labouring in the fields and herding the cattle, and illiteracy had decreed that parents were pupils too (often taught by their own children) – Chris was instrumental in grounding the communal educational policies that Frelimo had set in train. In Grenada (1980) he was summoned from Carriacou, where he was teaching, to the capital by prime minister Maurice Bishop to head the country’s teacher training programme – a white Englishman entrusted by a Black Power government with the education of the next generation! From there he went on, at the party’s behest, to help train its cadres – and set up and run the government’s publishing house.

And when the Americans came to destabilise the revolution, Chris was there at the falling barricades – an Englishman out of Kipling and the Boy’s Own Paper. An Englishman for all seasons.