An expanded version of a talk given by A. Sivanandan to the PDS’ Europäischer Kongress gegen Rassismus’, Berlin, 13-15 November 1992. Race & Class (34/3, January 1993)

So much I have heard today is redolent of the past. But we live in a changing world, and we must cast aside yesterday’s ideas, yesterday’s analyses, yesterday’s dogmas if we are to understand and withstand what is happening in our societies today. We may learn from the past, but we cannot use the perspectives of the past. We may have the same vision of the future, but we cannot work towards it on the basis of past strategies and past tactics — or with the aid of the same social forces, the same agents of change.

We have got to build socialism afresh, anew, from the circumstances of the present. We have got to fight racism, anew, from the circumstances of the present. And we have got to understand that, today, the fight against racism is also a fight for socialism.

How, then, should we understand this racism? And how fight it? What is the context of our times within which we should appraise it? What are the trends in society which help to create it?

We live in the throes of a technological revolution in which, instead of Labour being emancipated from Capital, Capital is being emancipated from Labour.

We live in the throes, not of a socialist revolution which has overthrown capital, but of a capitalist revolution that has overthrown socialism.

We live in the age of the information society when not the means of production, but the means of communication are paramount-and the creation of popular ideas and of popular culture is in the hands of the media and the government, the owners and controllers of the means of communication.

We live in a New World Order which is the old capitalist order without opposition, without contradiction – a New World Order in which the Second World has become the Third World and the Third World the site, once again, of primitive accumulation, of pillage and plunder, this time under the guise of IMF-and World Bank-*led’ growth.

We live in a period of unprecedented prosperity coupled with unprecedented greed, leading to an unprecedented maldistribution of wealth – and the establishment of the two-thirds, one-third society, the dog-eat-dog society.

More recently, we have moved into a period of economic recession when all these things become more accentuated, when those who have won’t give, and those who haven’t must take, and whom they take from are those below them – and so to the dog-eat-underdog society.

If these are the general contours within which we’ve got to locate and understand racism today, the way to fight it, and stop it from developing into fascism, must be understood in terms of its particular trajectory in the countries of post-war Europe. Because the racism of post-war Europe is not the same as the racism of the colonial period or of Nazi Germany.

Racism never stands still: it changes its basis, its function, its thrust at different times in different places in different ways. So, although traces of past racisms inhered in the post-war racism of Europe, the raison d’être of racism itself was not so much colonial domination or plain race hatred as exploitation – of the foreign and/or colonial workforce that a war-torn, labour-less Europe was forced to recruit for the purposes of post-war reconstruction. Racism — racist ideas, a racist culture – was there, ready to hand, in European civilisation. And it was inevitable, natural even, that it should be used to provide western Europe with the cheap captive, disposable labour – labour on tap – that it desperately needed.

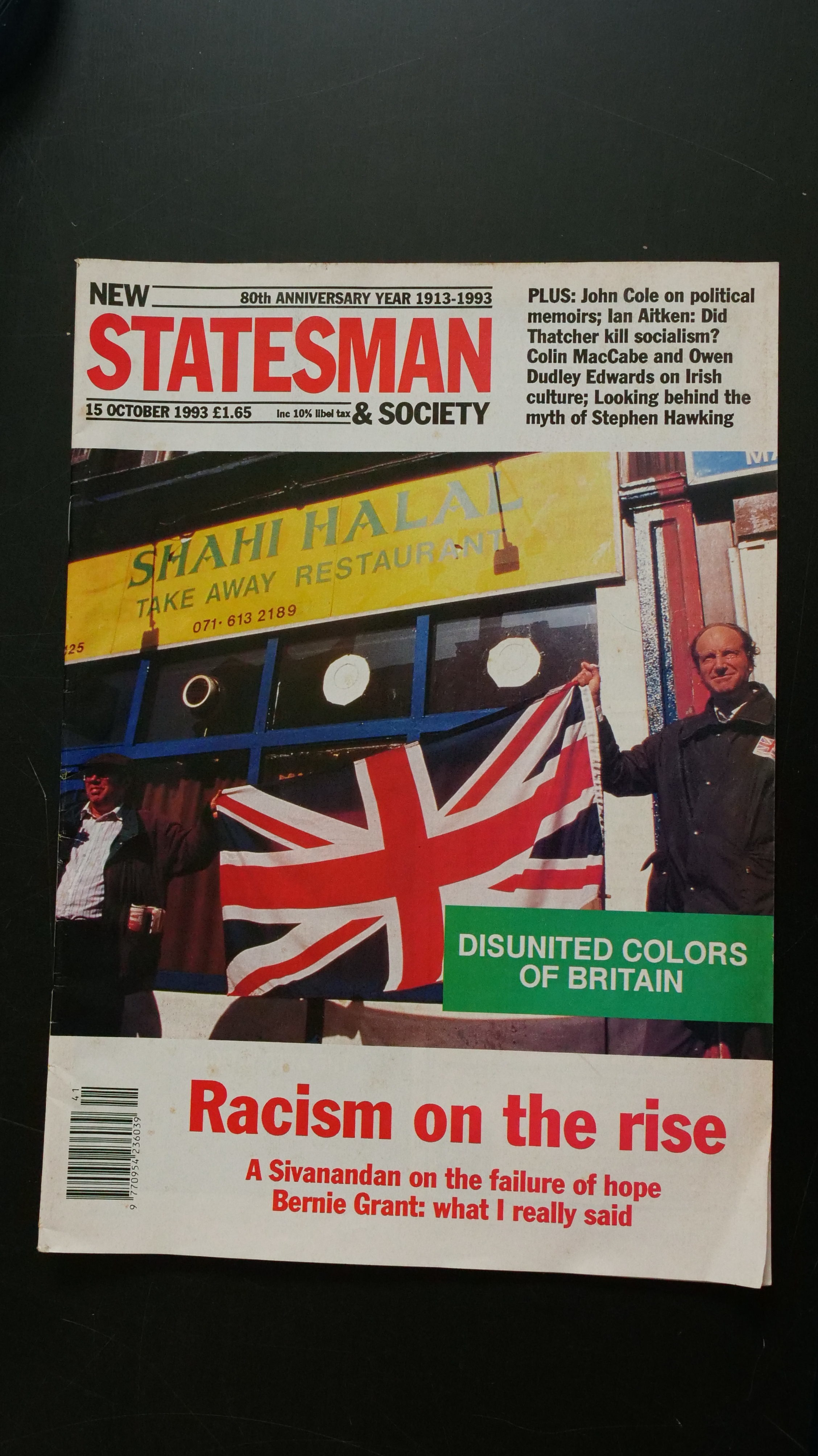

At first, such racial discrimination in countries like Britain (which had colonies to recruit its labour from) was left to market forces. But when, by the 1960s, such labour was no longer needed, racial discrimination got written into the immigration laws, into administration, into judicial decision-making. Racism became institutionalised in Britain as in the USA, it became respectable. The state had given its sanction to racism, and that, in turn, led to a wave of ‘Paki-bashing* and ‘Nigger-hunting’ and the rise of the fascist National Front. Racism had, in fact, become part of the political process through which MPs got elected and governments made.

Notes and documents 69 The history of that period has been recounted by me elsewhere (and is available in a German translation from Schwarze Risse Verlag), so I don’t need to go into it now. But the point I am trying to make here is that popular racism derives its sanction and its sustenance from state racism and that, in our time, the seed-bed of fascism is racism.

Countries like West Germany, which had no colonies to speak of, had second-class status woven into the gastarbeiter system. An institutionalised system of discrimination was there from the beginning, either written into the constitution itself and/or anchored in legislation relating to foreigners. And so a whole popular culture of xenophobia (I baulk at that word, I’ll tell you why later) grew up in West Germany, sustained by article 116 of the constitution — which, as you know, bases German citizenship on blood – and venerated by the state.

By the late 1970s, when Britain had entered Europe and had no need of the black Commonwealth, when the definition of Europe itself was of a Commonwealth of white nations, racism began to find new life not in the economic raison d’être of the post-war years, but in a new cultural exclusiveness, in a new white nationalism. Mrs Thatcher put it succinctly when, on the eve of her election as prime minister, she remarked that ‘we were being rather swamped by people of a different culture’. And the media took up her cry in lurid and lying detail and the white fascist maggots crept out of their woodwork to attack our women-folk and fire-bomb our homes.

The point I want to stress here — and over and over again – is that it is the politicians and the media and the state that create popular racism, and inhere it in the popular culture, and provide, thereby, the breeding ground for fascism. The fight against fascism, therefore, must begin in the fight against racism, in the community, and involve the whole community. Fighting fascism per se will not eliminate racism; but eliminating racism would cut the ground from under fascist feet.

Today, as we move closer and closer towards Maastricht, a new, common, market racism is beginning to emerge. The countries of Europe are drawing from the lowest common denominators of each other’s national racisms to formulate racist immigration laws and policies. That such laws and policies are being hatched in secret by ministers and officials and police chiefs in ad hoc committees of the Trevi group and at Schengen and Dublin, and not in the European parliament, bodes ill for the future of European democracy. But that they are laying the foundation for a new Euro state-racism bids fair to set us on course to a new Euro-fascism.

And because Germany is in the forefront of shaping the future destiny of Europe and sets the European agenda, what is happening in Germany is of vital concern to all of us. Hoyerswerda, Rostock, Eberswalde, Cottbus, Eissenhüttenstadt, Mannheim, Hünxe, Saarlouis (you see how easily the names trip off the tongue: that is what we know of Germany today, as we once knew of Germany as Buchenwald and Dachau) – they should not be happening at all. And all those deaths, of a Ghanaian, an Angolan, a Tamil, a Gypsy, something like twenty-five deaths in as many months, on the basis of their race, their colour, their difference? – they should not have happened at all. One death is a death too many.

But if these are horrendous crimes in themselves, what is more frightening is the official attitude towards them. In Hoyerswerda, the regional government, instead of protecting the refugee hostels against fascist attack and arresting the attackers, removed the attacked to refugee camps. After Rostock, chancellor Kohl and a whole host of leading figures found cause not to condemn the neo-nazis but to blame article 16 of the constitution for, in federal interior minister Seiters’ words, “this continuing flood of economic refugees’ – thus trans forming the nazi criminals into some sort of guardians of the community, and entering the country once more into the popular numbers game: the less refugees, the less fascists. The logical conclusion of which would be: no refugees, no fascists — which is not a far cry from the final solution’.

But if official attitudes compound the problem of racism and give a fillip to fascism, what is even more unnerving, in the long-term sense, is that Germany has not even got to first base in owning up to its racism or calling it by its proper name. Instead, you have terms like xeno phobia, the fear of strangers, and Ausländerfeindlichkeit, hostility to strangers, foreigners. But you had no fear of strangers when you wanted them to come and slave for you. Then you called them guest workers, another grand euphemism, and a misnomer, seeing the way you treat those guests by denying them residence and citizenship rights and keeping their German-born children for ever strangers and foreigners in their own country.

And why ‘hostility to foreigners’? Why not just plain racism – or, if you want to be more specific, anti-Semitism, anti-Arabism, whatever?

You see, xenophobia is the other side of the coin of homogeneity. The fact that the German nation is defined in ethnic terms and that that definition is enshrined in the constitution does not allow you to think of Turks, Moroccans, Angolans, Vietnamese, who have been living here for over a generation as anything but strangers, foreigners.

The insane injustice of that situation emerged very clearly recently when Eugen W, the son of a German Jewish father and a Romanian Christian mother, having returned to Berlin in 1982 and worked for a state-owned transport company for nine years, applied for citizenship – and was refused. Eugen appealed. In September 1991, the High Court conclusively rejected his application on the basis that he was ethnically Jewish and could not, therefore, be ethnically German.

The courts, too, do their bit in defining and refining Germanness.

The racism in the GDR, as in other communist countries, on the other hand, had never, to the best of my knowledge, been part of state policy as such. On the contrary: the state declared itself anti-racist. Its anti-racism, however, operated on a state-to-state level, and not on a people-to-people level. So that while the East German government welcomed Angolans, Mozambicans, Vietnamese, etc., to work or study in their country, they were still looked upon as foreigners and kept apart in hostels and barracks.

Hence, though East Germany’s anti-racism was part of state dogma, it never got translated into popular culture. People were prepared to be anti-racist and be helpful to other races, so long as they lived over there, in their countries. But their presence in East Germany, though tolerated (precisely because of state strictures), was resented by ordinary people, particularly in times of growing economic hardship.

The state never taught the East German people to accept different peoples, different cultures, let alone live with them. It was basically a monolithic state with a monolithic culture. What it did, though, was to hold racial antagonisms in check. But the moment the communist) state strictures were removed, the dogs of racism ran amok.

At the point of unification, therefore, you get both these racisms (the West German and the East) compounding each other. And the Kohl government, instead of alleviating the economic misery of East Germany which exacerbates racism, exacerbated racism further by offering up the anodyne of keeping refugees out and making Germany even more German.

And a whole school of thought has sprouted alongside this absurd notion: that it is the neo-nazi youth who are the real victims of their violence and should, therefore, be “therapeuticised’, ‘social-worked’ out of it. Which, apart from treating the victimisers as the victims and further sanctioning racial harassment and racial attacks, holds out also that racist behaviour stems from racist attitudes, without recognising, at the same time, that racist attitudes and racist behaviour stem from the material and social conditions in which young people are forced to live – and so shifts the burden of responsibility once more from society to the individual.

But such a misapprehension stems from the central belief that the youth are the agents of racist violence. Which is manifestly untrue. They are not the agents but the carriers of the virus. The agent is the state, the causes are unemployment, deprivation, poverty. If you want to socialise youth out of their racist behaviour, give them a stake in society. If you want to put a stop to their racist violence, outlaw racism, penalise racism, stop purveying the culture of racism, remove article 116 from the constitution.

For a start, Kohl’s government should be putting money into East Germany without taking it out of there and running it down; it should be sharing the prosperity of West Germany, instead of hogging it all, and that should do West Germany itself some good. For the nationalism of West Germany today is not the nationalism of the defeated but of the victorious, the economically victorious. It is the nationalism of prosperity, not of poverty – the nationalism of those who want to jealously guard their prosperity and carry on becoming more prosperous still – the nationalism of those who define poverty itself as culpable, if not genetic, hereditary, racial.

One wall has come down, another has gone up between East Germany and West: a colonial wall – and it’s the same wall that is going up against the rest of eastern Europe. The only difference is that the East Germans are refugees in their own country, economic refugees.

Refugees are made, not born. In the Third World, they are made by repressive political regimes installed and/or maintained by western powers to ease the path of foreign capital, MNCs, IMF and World Bank depredations. Free market economics have spelt the death of our countries. They create ecological devastation, population displacement and poverty for the many, and riches for the few. And poverty creates political strife and political repression, and political repression creates political refugees.

In trying to distinguish between economic refugees and political refugees, therefore – and it was Germany that first made the distinction in 1987 when it wanted to expel the Tamils – you have missed out a whole series of steps in the process of how economic refugees became political refugees. You have missed out on the basic truth that your economics is our politics. And the intake of refugees, therefore, must be based on need, not numbers.

Similarly, the refugees from eastern Europe. For well on fifty years, the West has kept battering on the doors of the East to break down Communism and let Capital in. And when it succeeded, precisely because the command economies could no longer feed their people, it turned its back on them as well and let them fight each over over what little was left – only this time the fight was defined in nationalistic terms: poverty had become ethnic.

The West must either put money into these countries or let their people come to it. It can’t go round the world robbing people blind without the world arriving at its doorstep.

In that context, what I find the most encouraging thing about Germany is its article 16 which, though it does not give a right to seek entry, allows all who reach Germany to claim asylum there. And instead of Germany getting rid of that clause and going down to the level of Britain and the rest of Europe, the rest of Europe should rise up to Germany’s example and give refugees and asylum-seekers a chance to make their case in the same way.

Similarly, Germany and the other countries in Europe could do with the sort of anti-discriminatory laws (but with more teeth in them) that obtain in Britain.

Let the nations of Europe draw on the highest common factors of each other’s immigration and race policies and give us a charter worthy of the values and mores of European civilisation.

As for the charter, my organisation in London and some of the anti racist groups here have drawn up a 15-point programme [published below).

As for values and mores, we live today in a moral vacuum caused by the collapse of the working-class movement. The tension between Capital and Labour, which created liberal values and liberal freedoms, is gone.

Today, the new moral values will have to be forged in the tension between democracy (economic and political democracy) and nationalism/fascism – on the battlefield of democracy against fascism.

And that is where you and I come in. That is where socialism comes in. For socialism as an economic system may be over. Socialism as an oppositional culture may be fading. But there is still socialism as a faith, a creed, beliefs, values, traditions: loyalty, comradeship, solidarity, a sense of sacrifice and service, a sense of community, a feel for the less well-off, a passion for justice – all the great and simple things that make us human. Socialism, my friends, is not the past. Socialism is the future.