Racism never stands still. It is never of a piece. It changes its shape, its inscape, its function with changes in the economic system, the social forces that the system throws up and the hegemonic culture it exudes. Equally, the resistance to racism, the struggle against it, and the organisations that spring up to carry on that struggle also change. And nowhere is this clearer than in the struggles of the Asian community against the various avatars of racism: the crude racism of the working class, the genteel racism of the middle class, and the violent racism of the fascists. Each of these in turn had its own trajectory and was fought in terms of its own particularities. But they also had repercussions in, and the engagement of, the community, so creating both communal solidarity and continuity of struggle. Thus the first generation struggles of Asian workers on the factory floor, against trade union racism in particular, forced them to resort to unofficial strikes which needed the economic support and the political solidarity of the community.

Similarly, the racism meted out to middle-class African-Caribbeans and Asians in terms of discrimination in jobs, housing etc., though fought largely on the basis of lobbies, petitions and commissions of inquiry, resulted in equal opportunities policies and the Race Relations Acts.

But the struggle against racial violence which, in the Paki-bashing era of the ’60s had itself been ad hoc and defensive, was in the late ’70s transformed by the organised violence of the National Front (NF) against the Asian community into organised militancy against it by Asian Youth Movements.

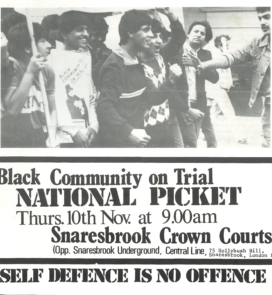

Significantly, it was the racist murder of 18-year-old Gurdip Singh Chaggar (in June 1976) in the heart of Southall — right opposite the Dominion Cinema, a symbol of Asian self reliance and security – that triggered off the militant politics of the Asian youth. A number of lost self defence cases had convinced the youth that there was no point in looking to the police or the courts for protection, let alone justice. And they saw the invasion of Southall as a violation too many. A meeting was held and the elders went about it in the time-honoured way, passing resolutions, making statements. The youth, however, marched to the police station demanding redress, stoning a police van en route. The police arrested two of them. The demonstrators sat down before the police station and refused to move until their fellows were released. They were released. The following day the Southall Youth Movement (SYM) was born, and the cry of ‘Self defence is no offence’ gave way to ‘Here to stay, here to fight.’

The SYM gained an immediate following in local schools and youth clubs and physically kept racism off the streets of Southall. In 1978 it picketed the Hambrough Tavern, a notorious meeting place for racists. And, in the wake of the politics of SYM, the whole Southall community turned out on April 23rd 1979 to stop the NF celebrating St George’s Day in their town hall. But the police declared the town centre a ‘sterile area’ penning the demonstrators between three double police cordons, and in the ensuing melee Blair Peach, a white anti racist and teacher, was bludgeoned to death by a Special Patrol Group officer.

On July 3rd 1981, three coach-loads of skinheads descended on Southall for a concert at the Hambrough Tavern and, on the way to the pub, smashed shop windows, terrorised shopkeepers and shoppers and attacked an Asian woman. Within an hour several hundred Asian youth gathered at the Hambrough to send the skinheads packing. Police arrived to protect the skinheads from the anger of the town’s youth. The evening ended with the Hambrough set on fire and the skinheads gone.

Police harassment and fascist violence, boosted by Thatcher’s ‘this country might be rather swamped by people of a different culture’ speech and her partiality for state thuggery to resolve civic problems, led also to the formation of similar Asian youth organisations and defence committees in London, Manchester, Leicester, Bradford, Nottingham, Sheffield, Burnley and Birmingham. Several of them sprang up in London alone – in Brick Lane after the murder of Altab Ali and Ishaque Ali, in Hackney after the murder of Michael Ferreira, in Newham after the murder of Akhtar Ali Baig. And, like the Black strike committees of an earlier period, the youth groups moved around aiding and supporting each other joining and working with African-Caribbean groups in the process, sometimes on an organisational basis (SYM and Peoples Unite, Bradford Blacks and Bradford AYM) sometimes as individuals coalescing into political groups such as Hackney Black People’s Defence Organisation and Bradford’s United Black Youth League (See A. Sivanandan, ‘From resistance to rebellion’ in A Different Hunger, Pluto, 1983.)

Of these, the landmark case was that of the Bradford 12 (in 1982), the trial of twelve Asian youth who made petrol bombs to defend their community against an impending attack by the NF, and were charged with conspiring to make explosives with intent to endanger life. But their plea of community self-defence was accepted by the jury and all twelve were acquitted.

Of course there were differences in the composition of the groups and in the larger politics they espoused. In general, the AYMs grew out of local friendship groups (or gangs) formed in schools and clubs. In some cases the movement consisted predominantly of one group e.g. Punjabi Sikh in Southall, Bengali Sylheti in Tower Hamlets. But in Birmingham and Bradford the AYMs were more diverse, crossing not just regional and religious divides but, more significantly, because they included in their number young Asians who arrived with a political (Marxist) background via a disillusionment with ‘White Left’ politics, political divides as well.

Left politics, usually Trotskyist, had frustrated its young Asian recruits by the way it had subsumed race to class and the fight against racism to the ideological fight against fascism. They lived class, but felt race: racism invaded their lives. It was their most plangent experience – and out of that experience came the undertaking to fight racism and, therefore, fascism, not fascism and perhaps racism. But it was they who were instrumental in bringing to the youth movements an understanding of class, state power and international solidarity.

And it was this infusion that broadened what were originally parochial ethnically based movements into a larger Black politics. Though they mobilised in terms of the specific way that racism impacted on their communities, in the fight back they were Black. This unique sense of Black as a political colour like Red (rather than a skin colour) had emerged in Britain at the end of the ’60s from a common history of colonial oppression, a common experience of racism and a common fight against it. And the ‘international interest that the first generation had in their home countries (fighting Mrs Gandhi’s Emergency or Pakistan’s military dictatorship) was now reincarnated as a solidarity with oppressed groups from Jerusalem to Johannesburg.

What the AYMs (with the honourable exception of Manchester) failed to address, however, was the sexism in their ranks and the patriarchal structure of their organisations. Subsequently, their active participation in anti-deportation and family reunification campaigns, mainly women and children, helped some of them to recognise their shortcomings in this area.

In sum, the Asian Youth Movements cut across cultural boundaries and religious divides. Born, by and large, in Britain, to working-class parents, whose customs were arcane and religion a refuge, the second/third generation tended to be secular of outlook and political of culture. The fight against racism was not a fight for culture. Conversely, the fight for culture did nothing to combat racism.

But Lord Scarman in his report on the ‘Brixton disorders’ of 1981 put ethnic disadvantage as the cause of the riots. The solution for which was ‘positive action’ on the part of local and central government to improve the lot of disadvantaged ethnic groups. Which in practice took the form of equal opportunities policies and ethnic head-counts for the up-coming Blacks and a ‘samosa and steel-band’ culturalism, replete with community centres for the up rising Blacks. The former led to fights for office and descended into equal opportunism, the latter served to break down political black into its cultural constituents scrabbling for ethnic hand-outs. Already, an unofficial laissez-faire multiculturalism had begun to make inroads into the anti-racist movement.

Scarman now made it official. In one stroke he had dismissed institutional racism and institutionalised multiculturalism in its stead.

It only remained for the Rushdie affair (1989-93) and the consequent upsurge of anti-Muslim racism to break down the secularism of the youth movements and drive them into the alley-ways of their parents’ religion.

But in the long fight against racism, AYMs have left their mark, most importantly in the matter of turning cases into issues and issues into a movement – a legacy which has been taken up by the Stephen Lawrence Family Campaign and has served to place institutional racism, once more, at the heart of anti-racist struggle.