Published in Race Today April 1971

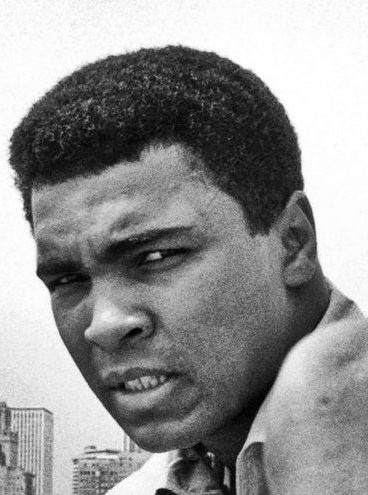

There is no set-back in history except that we make it so. Tonight the black world weeps that their king has passed away. But tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow…every black man will have become his own king – for that is the legacy that Muhammad Ali leaves us even as he leaves the ring.

The white world had willed that the king should die. But it took the might of the most powerful, the most designing judicial system in the world to bring the king down. Joe Frazier was the unreckoning tool of that design.

Heavyweight boxing had, until the advent of Muhammad Ali, come to be associated with brute force. If it once had been the province of elegant gladiators like Gentleman Jim Corbett, it was as the sport of white men. But as the black man began to claim the game more consistently, the game itself became tainted with the stereotype image of the nigger. It was a thing for brutes – hefty, slow-moving, slow-thinking, sub-humans – a blood sport from which the white man would gather profit and pleasure at no great cost to himself. It was satisfying too, to his psyche, if he could gather the myriad frustrations that in his daily life he visited on niggers in general and embody them in a single super-nigger. Two super-niggers would be doubly cathartic-and the more explosive they were, the more orgasmic his release.

At worst it was a game of make-believe, a confidence trick wherein the Thing, by being allowed to become a Super-Thing, believed it passed for man. Or so it would have seemed-until the black renascence of the sixties. Even the civil rights strugglehad only served to cordon off the black athlete in a bantustan of sport. It was left to Malcolm X and the black power movement to threaten the total release of the ‘Negro.

Muhammad Ali is the finest epitome of that release. And it is this that bugs white society so. He is not just a prize-fighter, he is not even one man. He is many men in one-and all of them black. Out of the very blackness, which white society decrees as evil, he squeezes out an image of himself and of his people which is both peerless and profound. Out of the very handicaps inherent in the medium he works in, he reconstructs a style which is also the life style of his people. His people dance, he dances. His people sing, he sings-in verse. His people stand with wearied heads, he brings them erect again. His people bravetheir broken bodies, he gives a swagger to them. And to the sport itself-to the most heavy-footed sport of all-he brings an artistry unsurpassed by Pavlova. Out of an elegy he makes a hymn.