Xenophobia

There is no such thing as xenophobia. Xenophobia is a western construct which came into being during the capitalist phase of ‘western civilisation’. You fear strangers because you are afraid they will take your property, land, goods. And private property came into being with capitalism. Pre-capitalist societies, feudal societies, were happy to welcome strangers – certainly the pre-capitalist societies of the Third World. Our civilisations, our cultures always welcomed strangers. That is how Lobengula lost his country to the Europeans; that is how the native Indians of America lost their lands to the whites; that is how the Portuguese, Dutch and English each gained a foothold in my own country, Sri Lanka. (Remember the old saying about how, when the missionaries came to Africa, they had the Bible and you had the land and when they left you had the Bible and they had the land?)

Xenophobia is a term which implies that there is something innate, everlasting, natural even, in this fear of or phobia against ‘others’. It is human nature, innocent, not man-made and culpable like racism. In Europe, where it is increasingly used to explain away the mistreatment of asylum seekers, it has become the acceptable face of racism. For all these reasons, I reject it.

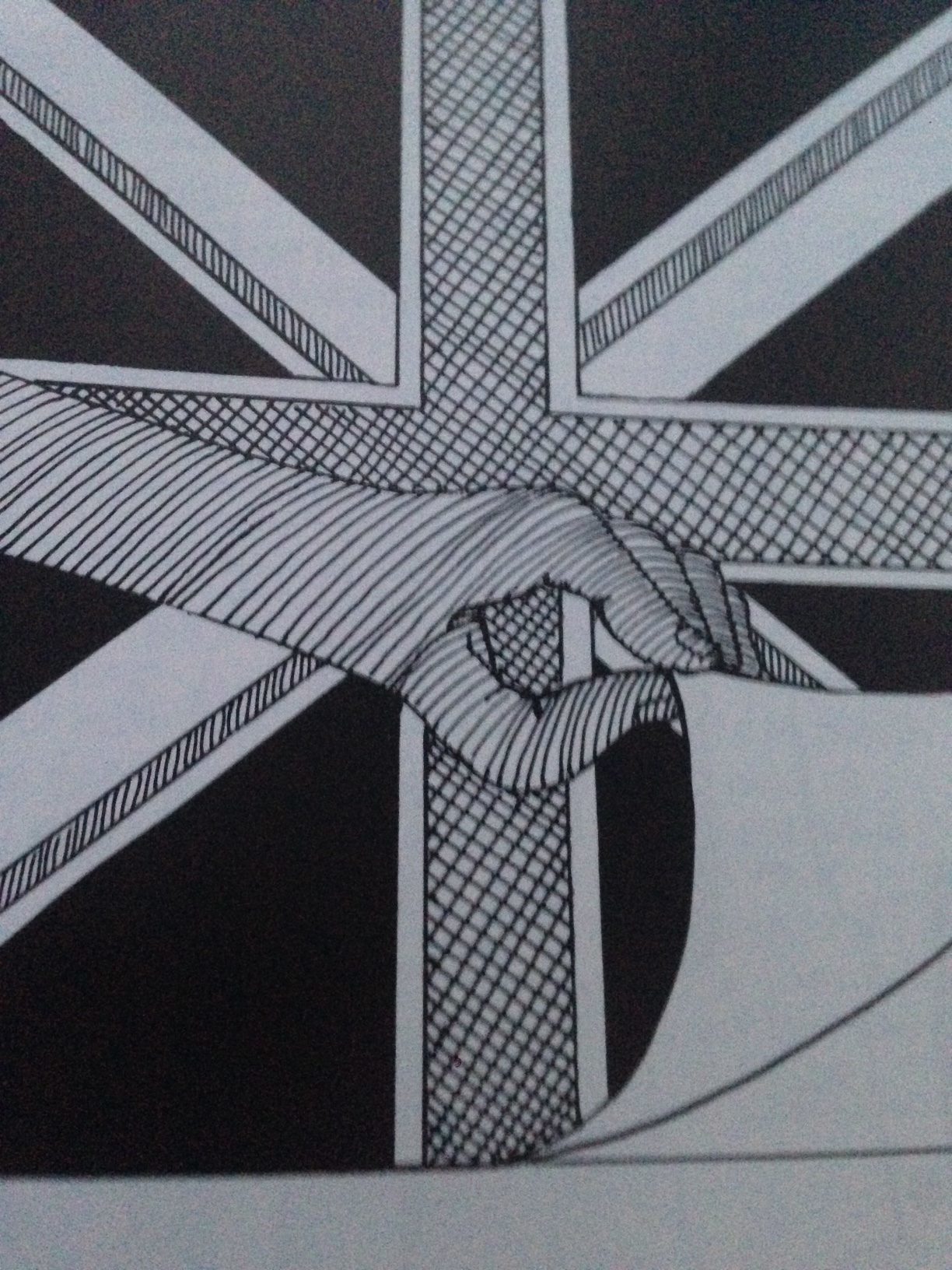

Then, there’s the other side of the coin of xenophobia: the defence and preservation of ‘our people’, our way of life, our standard of living, our ‘race’. That is why I have been contesting the term xenophobia in the European context and have coined the term xeno-racism for what is going on here. For in the way it denigrates and reifies people before segregating and/or expelling them, xenophobia bears all the marks of the old racism, except that it is not colour-coded. It is a racism not just directed at those with darker skins, but at the newer categories of the displaced and dispossessed whites, who are beating at western Europe’s doors, the Europe that displaced them in the first place. It is racism in substance but xeno in form. It is xeno-racism.

Racism does not stay still; it changes its shape, size, contours, agency, – with changes in the economy, the social structure, the system. But it is and has always been an instrument of discrimination. And discrimination has always been a tool of exploitation. Racism, in that sense, has always been rooted in the economic compulsions of the capitalist system, but manifests itself, first and foremost, as a cultural phenomenon, susceptible to cultural solutions such as ethnic education and identity politics. Redressing the problem of cultural inequality, however, does not by itself redress the problem of economic inequality. Racism needs to be tackled at both levels – the cultural and the economic – at once, remembering that the one provides the rationale for the other. Racism, in sum, is conditioned by economic imperatives, but negotiated through cultural agency: religion, literature, art, science, the media and so on.

Which of these agencies, though, holds sway in a particular epoch is itself dependent on the economic system of that epoch. Thus, in the period of primitive accumulation, when the pillage and plunder of the new world by Spanish conquistadors was laying the foundations of capitalism, it was religion in the form of the Catholic Church that gave validity to the concept that the native Indians were ‘sub-homines’, the children of Ham, born to be slaves, and could therefore be enslaved and/or exterminated at will. In the period of merchant capital, when the monarch was no longer subordinate to the Church and the bourgeoisie was in its ascendancy, the racialist ideas of the earlier period became secularised in popular literature, political discourse and education and served to rationalise and justify the trade in black slaves.

With the development of industrial capitalism and its corollary, colonialism, the racialist ideas of the previous epochs congealed into a systemic racist ideology to condemn all ‘coloured’ people to racial and cultural inferiority. By the end of the nineteenth century, at the height of the imperial adventure, the ideology of racial superiority began to take on a pseudo-scientific validity in the Social Darwinism of Gobineau and Chamberlain – which in turn further popularised the view of racial hierarchies.

Today, under global capitalism which, in its ruthless pursuit of markets and its sanctification of wealth, has served to unleash ethnic wars, balkanise countries and displace their people, the racist tradition of demonisation and exclusion has become a tool in the hands of the state to keep out the refugees and asylum seekers so displaced on the grounds that they are scroungers and aliens come to prey on the wealth of the West and confound its national identities. The rhetoric of demonisation, in other words, is racist, but the politics of exclusion is economic. Demonisation is a prelude to exclusion, social and therefore economic exclusion, to creating a peripatetic underclass, international untermenschen.

Once, ‘they’ demonised the Blacks to justify slavery. Then they demonised the ‘natives’ to justify colonialism. Today, they demonise the poor and the alien, the displaced and the dispossessed to justify the ways of globalism. And, in the age of the media, of discourse, of spin, demonisation sets out the parameters of popular culture within which oppression and exploitation find their symbiosis.

In the Manichaean world of global capitalism, where there are only the rich and the poor – where the national state works primarily in the interests of multinational corporations, where the national bourgeoisie collaborates with international capital, where the middle class is effete and self-serving and the working class has lost its political strength – poverty not race is the mortal sin. Poverty is the new Black.